War Stories…Sort Of

California Conversations

Published Issue: Summer 2011

Shirley Marie Burns was born into a military family, became a nurse and a soldier herself, married an army man, spent most of her life travelling from assignment to assignment until after ten months of asking for the opportunity, personnel sent her in the middle of the 1960s to a distant post in Vietnam.

In her own words:

My orders got me to San Francisco, and then I had to fly ‘standby’ to Vietnam.

My tour was tiring and sad, yet the most rewarding time of my life. I arrived at Tan Son Nhut Airport in Saigon. I was dressed in winter greens and high heeled shoes.

The nurses were taken to the Post Exchange and told to buy all the feminine things we would need for one year.

After lunch at the Officers’ Club we put on helmets and flack jackets and boarded a bus for Cu Chi. We were escorted by several armored vehicles with helicopters overhead.

I worked with a group of other nurses at Cu Chi to set up the 12th Evacuation Hospital, a M.A.S.H. unit basically, although that term was not used at the headquarters for the 25th Infantry Division.

It was muddy everywhere and wet. It seemed to just suck you down into it. Our new living quarters, our hooches, had wood sides and a tent top. The guys could not wait to show us our new restroom, our outhouse. They had built them and put pink toilet seats over the holes. They were thrilled and most of us started crying.

I was promoted to 1st Lieutenant.

Working in the rain and mud, it took nearly a month to open for business. Then the business came...and kept on coming. My life was never the same.

The next few months were a series of highs and lows.

The kids...bloody, dirty, hurting, wanting the nurses to hurry so they could get back to their unit, to their buddies.

The MedEvac helicopters were nearby at all times, day and night. We had twelve-hour shifts...when we had shifts at all.

There were trips to the surrounding villages to dispense medicine. When the pills we gave away started showing up with captured Viet Cong, we gave only injectable meds.

The mortar attacks were a part of working at Cu Chi. There was a direct hit on my ward and it killed two GIs instantly. That seemed so unfair.

The highs were less numerous, but the contrast seemed so remarkable. R&R in Penang and Tokyo, the mai tai party when the new general took over the 25th Division, the guys coming over from base camp with steaks just to say, ‘thank you.’

Shirley served as the first female commander of the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) in the State of California. She also chaired the California VetFund Foundation.

By the middle of 1967 the Vietnam War was ramping up and the stories of the bloodiest battles were being shown on American television. The TET Offensive, the cruelest battle of the war, was less than a year away, and Walter Cronkite, the venerable television newscaster, was about to say that our goals in Vietnam were untenable.

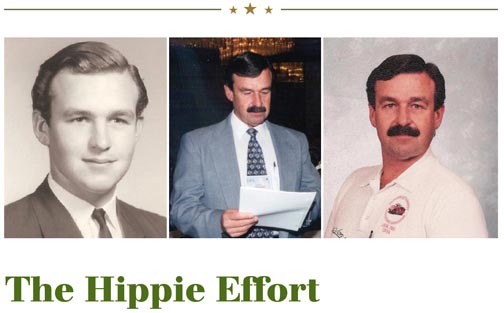

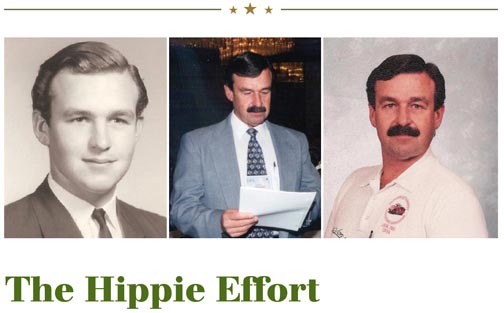

Ray Snodgrass was a recent high school graduate working the fire season for CAL FIRE when he got the notice to report for his army physical. His mother cried at the prospect of Ray going to war and her tears were not lessened when the doctors told him he was 1A and physically fit to serve in Southeast Asia.

A month later Ray was told to be at the induction center for his swearing-in. He got his release from CAL FIRE with the promise that he could work for them again as soon as his time in the service was complete.

On the morning of his arrival at the induction center, Ray was outside in a long line of new enlistees.

Before they could all make it into the building there was a ruckus. Several long-haired, colorfully dressed young people began making noise and forcing their way into the induction center ahead of the draftees. It is almost quaint to admit it now, but there really was a time when hippies existed as part of a peace movement that was sweeping the country. There was a skirmish; it almost got violent before the hippies ran down the street screaming that the war needed to end. They had stolen papers from the counter and were waving them in the air.

Ray eventually got invited inside. He was told to stand in place while names of the new draftees were called out and they were sent through a second door to be sworn in. There were a half-dozen young men left in the lobby when the soldier in charge asked each of them their name. Ray was one of them.

“The hippies stole your files,” the soldier told them. “We can’t take you into the army today. You need to come back and have another physical and begin the entire process all over again.”

“How long will something like that take?” Ray asked.

“We’ll call you.”

It was another month. Ray went back to the induction center as he was told, and a new doctor did the physical. This time the doctor noticed that Ray’s small toe on his left foot was bent and crossed over the toe next to it.

“Is your toe always like this?” the doctor asked.

“Yes.”

“Do you remember when this first happened?” the doctor asked.

“Yes, I broke my toe jumping off the back of a pickup truck when I was six years old.”

“It is a deformity,” the doctor told him.

“I don’t even notice it.”

“It will be impossible for you to live an entire year in combat boots,” the doctor opined.

“I wear boots on my job,” Ray answered.

“Combat boots are for marching,” the doctor snapped.

Ray was declared ineligible to serve in the military. He was sent home without an option to appeal.

The hippies who had awakened that day with the intent of interrupting the military had managed to change Ray’s life.

All of the draftees who Ray was supposed to join on that first trip to the deployment center were immeasurably altered by going to war. Many of them died. All of them were different because of the experience.

Ray went back to work the following week. He would have a remarkable career in the fire service. He would twice be selected Firefighter of the Year, and two decades after his dismissal from the induction center he was elected by his peers to be president of CDF Firefighters.

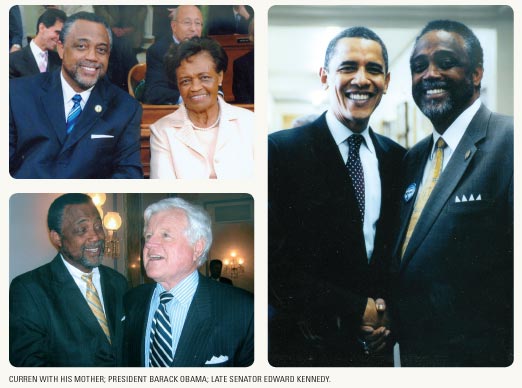

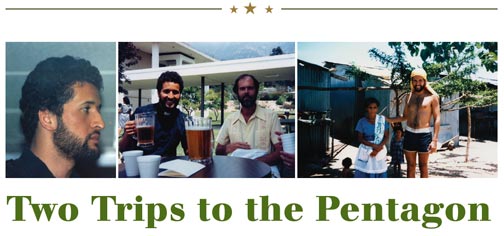

Years before he decided on a life in public service, Juan Vargas had a higher calling. The Senator was a Jesuit seminarian, a young man who actually spent time living in a cell vacated years before by another Jesuit seminarian, Jerry Brown.

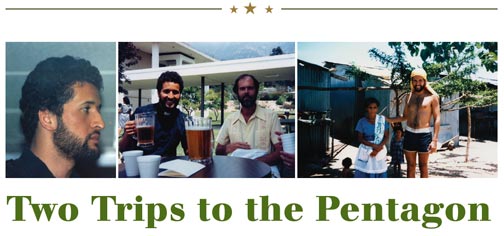

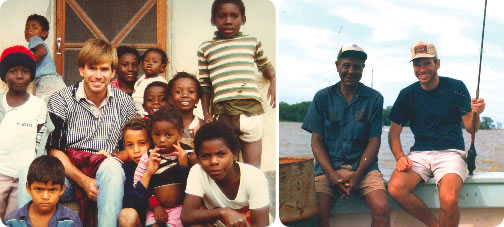

Juan has always held a special interest in South America. Part of his mission was spent in that war-torn continent bringing a message of service and peace. On his return, he joined a group of other Jesuits on a trip to the Pentagon to protest American intervention in El Salvador. It did not go well. There was a confrontation as they marched. Juan was arrested.

It is a long road to the priesthood. There are many chances to change one’s mind.

Juan kept his faith, but eventually left the Jesuits. He went back to school and was accepted to Harvard Law School.

While at Harvard, he played basketball and became friends with another student named Barack Obama.

The story, of course, is that Obama managed to get himself elected President of the United States.

A third friend of theirs from Harvard wanted an appointment from Obama. The President offered him Undersecretary of the Navy.

Juan was invited to the Pentagon for the swearing-in ceremony of the Undersecretary. He arrived and amidst heavy security got into line. He noticed a young woman, a second lieutenant, near the front of the line holding up a sign that said “Juan Vargas.” He got out of line and introduced himself to her.

She told him to follow her and they bypassed the other soldiers standing guard near the machines where everyone else needed to pass.

“Have you ever been to the Pentagon?” the young second lieutenant asked Juan.

“I have,” Vargas answered. “I’ve just never been inside.”

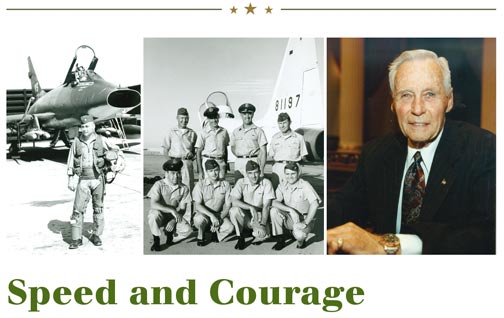

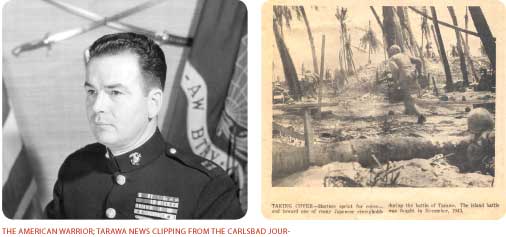

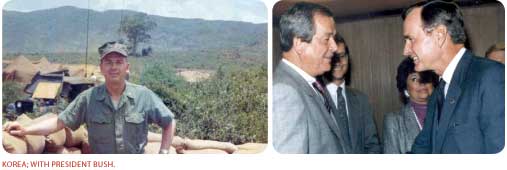

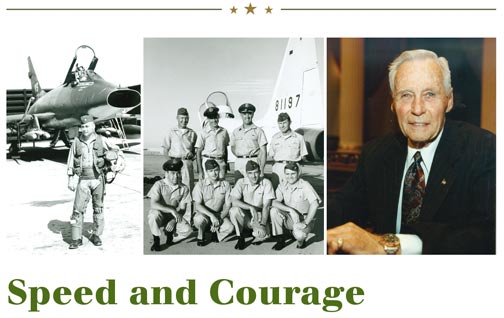

Assemblymember Steve Knight was born at Edwards Air Force Base, a former water stop for the Southern Pacific Railroad, on the borders of Kern and Los Angeles counties. The base itself was named after a test pilot who perished along with five others in a tragic mission that tried unsuccessfully to stretch the limits of aviation technology.

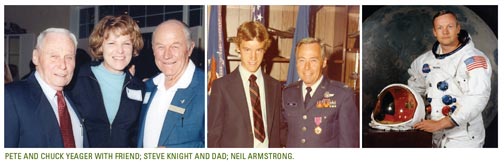

It makes sense that Steve breathed his first breath on a military base. His father, a state assemblymember and senator in his twilight years, was the legendary test pilot Pete Knight.

It is impossible to put the challenges Pete Knight faced into perspective. At a time when test pilots were dying at a rate of one per week, Pete Knight was in the middle of a brilliant thirty-year Air Force career that would see him test experimental aircrafts that no one had ever flown before. He would also fly in excess of 250 combat missions in Vietnam.

No one has ever flown an airplane faster than Pete Knight. Ever.

Forty-four years ago Major Knight flew an X 15 A-2 at more than 4,500 miles per hour or just shy of seven times the speed of sound.

He took the aircraft 281,000 feet into the air and earned the extraordinary distinction of becoming an astronaut for flying an airplane in space.

“My dad rarely talked about his accomplishments,” Steve says. “I remember one time being on a commercial flight with Dad when a passenger started talking about various experimental airplanes.

Even I could tell it was all bluster and he had no idea what he was talking about. My dad just sat there expressionless. He refused to straighten him out while I wanted to explain to the guy that he was in the wrong company to be pretending his expertise.”

The test pilot fraternity is unique. You can’t sit on a commercial flight and talk your way in. There is no honorary group. It is not possible to imagine the independence and courage it takes to climb alone into the cockpit of an airplane that no one is sure how it will behave, a plane that is designed to go higher and faster and move with greater singularity than any other type before it, and fly at great speeds and altitude to find out if it works.

The astronaut, Gordon Cooper, the final member of the Gemini team and the seventh American to fly solo in space, was asked once who he admired most. He answered something to the effect that the greatest men he ever met were those who had the courage to get into a hurtling piece of metal and make it fly according to specifications.

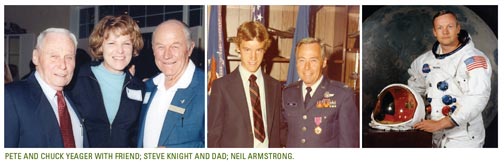

The first test pilot to break the sound barrier was lionized in the movie “The Right Stuff.” He was Chuck Yeager. He was a war hero who distinguished himself in Germany and Asia. A man noted by his colleagues for his abilities and his daring. General Yeager spent his long career flying combat missions and, later, test flights. He commanded squadrons and he flew solo, and with both daring and panache he was an ace who was admired greatly by his fellow pilots long before he became famous.

The first man to step on the moon flew experimental planes before he bounced on the lunar surface on July 20, 1969. A naval aviator and an engineer, Neil Armstrong was known for being self-effacing in spite of his many accomplishments. He was a combat veteran in the Korean conflict and, like Knight and Yeager, he was an old pro from the test pilot Mecca of Edwards Air Force Base. Armstrong would fly thousands of hours in complex aircrafts before he was chosen for his high-profile mission; and like all of his colleagues, find close friends among those who did whatever their country asked of them and did not always survive the task.

Steve Knight remembers a time when his dad attended a funeral service for a pilot friend. Steve was invited along. Afterward, Pete Knight invited Chuck Yeager and Neil Armstrong back to the house. The three great men sat in the kitchen for hours drinking beer and talking about old times. Steve sat in the kitchen with them.

“What did you say to them?” we asked Steve.

“Nothing, not a word,” the Assemblyman answered. “I just listened and it was one of the best days of my life.”

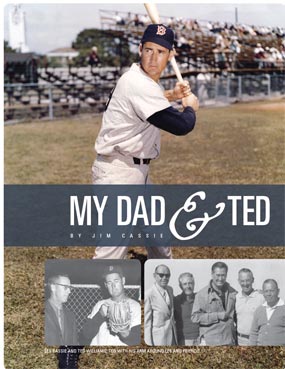

My Dad and Ted

Jim Cassie

Published Issue: Summer 2011

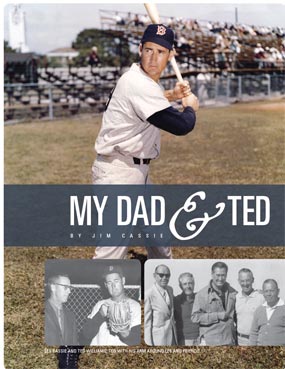

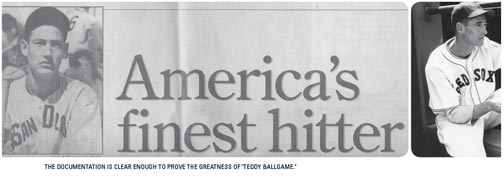

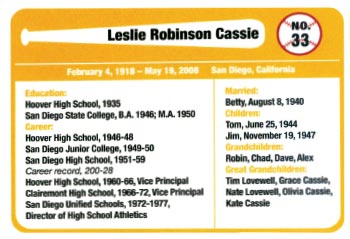

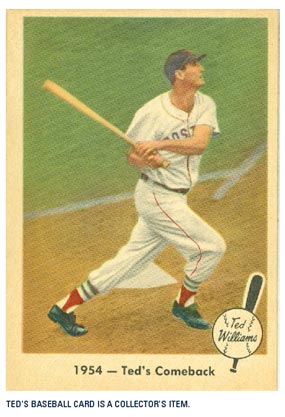

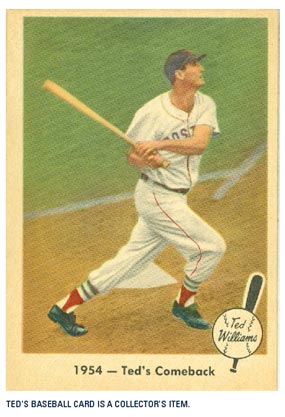

In the early years of the Great Depression, two kids from San Diego, a great guy, my father, Les Cassie, and a future baseball legend and war hero, Ted Williams, developed a close friendship.

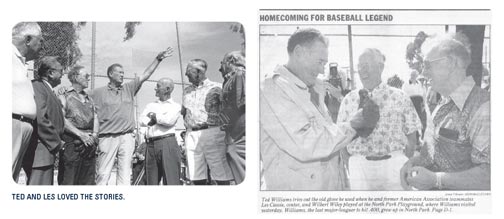

They grew up during a time when two boys could get up early and find a day-long game at the then University Heights Playground, where foul balls ended up too often in a reservoir; or the Central Playground, a place neighborhood rivalries played out with an intensity that was largely unnoticed by most adults, since their supervision was not needed by boys playing baseball in the 1930s. It was a time and a place that no longer exists. Ted Williams would remember San Diego as ‘the nicest little town in the world.’ The home runs were hit into the yards of bungalows that were razed to make room for the newcomers. The San Diego of their youth was still somewhat rural, less than 200,000 people in a community where more than three million crowd today. The homes on Utah Street were affordable, if a bit run down, for a single mother. The people who bought the house at 4121 Utah Street almost fifty years after Ted’s mom bought it still boast that they also own the kitchen table on which Ted Williams signed his first major league contract.

Baseball

Baseball mattered to the boys. They played it every day with guys named Roy and Wylie and a big kid named March who was always chosen first. The professional teams they followed were all on the eastern side of the country and could be heard on the radio or read about in the morning and evening newspapers, and all of this was done in a smaller world and without ever knowing that television, let alone something like cyberspace, would be in anyone’s neighborhood.

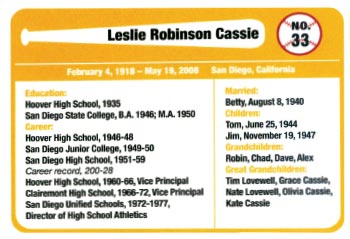

Clearly, the common bond for these two friends was baseball. For Ted, it was hitting a baseball. Eventually, for my dad, it was teaching kids how to hit a baseball. And for me, it was a wonderful experience to see this long friendship up-close, all wrapped around the quietly optimistic decade of the 1950s. It was a marvelous time, although we didn’t appreciate it at the moment for all of its wonder. This story is about my dad, Leslie Robinson Cassie and his friend, Theodore Samuel Williams.

Records indicate that Ted’s given name was Teddy, for the first President Roosevelt, but later changed to Theodore. Ted’s mother, May, was of Mexican descent and seemed to find greater satisfaction working long hours for the Salvation Army than putting in time being a mother. She was once named San Diego’s Woman of the Year. It was complicated. Ted loved her. He said during a visit back to San Diego in 1992 that when he first started playing ball he finally had enough to eat. After that, he fixed up his mom’s house. Ted was really quite proud because he wanted his mother’s house to look good. It wasn’t always easy. Regardless, among the many honors Ted earned, he deserves to be recognized as the greatest Latino baseball player of all-time.

Both Les and Ted grew up in the North Park section of San Diego. They played on the same teams throughout their teen years. In September of 1932 they were among the 351 sophomores that entered through the High Tower of Herbert Hoover High School. Three years later, their yearbook boasted that amidst a battery of floodlights and flowers, 241 graduating seniors, strong, self-reliant men and women, were sent forth to meet the world. Out of the thousands of personal stories that must have existed for those kids, one of the few still surviving is that Ted Williams was so into hitting he actually carried a bat to class.

For whatever reason, Ted’s father was not around much. Ted ended up spending a lot of time with my grandparents. My dad was not a fisherman, but Ted and my grandfather spent hours on San Diego’s seaside piers trying to hook the big one. Both Les and Ted were skinny kids for their age. This is in part how Ted later got one of his more famous nicknames, The Splendid Splinter. He was also known as Teddy Ballgame, The Kid, and the Big Thumper.

For whatever reason, Ted’s father was not around much. Ted ended up spending a lot of time with my grandparents. My dad was not a fisherman, but Ted and my grandfather spent hours on San Diego’s seaside piers trying to hook the big one. Both Les and Ted were skinny kids for their age. This is in part how Ted later got one of his more famous nicknames, The Splendid Splinter. He was also known as Teddy Ballgame, The Kid, and the Big Thumper.

Not unlike teenage boys of every age, Ted and Les wanted to get bigger and stronger. A normal summer evening in 1933 was spent with the buddies shooting games of snooker, having a milkshake at the drugstore, and then jumping on the scales. Over the course of that school break neither of them gained a pound.

They both played organized baseball. Ted was brilliant, and quickly caught the eye of professional scouts. In 1935, he graduated early, in December, before the rest of his class, and signed a minor league contract with the independent San Diego Padres of the Pacific Coast League.

The following year, Ted Williams signed with the Boston Red Sox organization and was immediately placed in their farm system.

The following year, Ted Williams signed with the Boston Red Sox organization and was immediately placed in their farm system.

Ted had rarely traveled as far as the neighboring San Diego communities, let alone to the major league facilities in Florida. So, the boy who would become the great Teddy Ballgame and my grandfather, who was a carpenter for the San Diego School District, boarded a bus bound for Sarasota, Florida. During the trip, an already painfully skinny Ted became ill and the two of them were forced to stay a few days in New Orleans until Ted could be nursed back to recovery. That year was the last one where Ted Williams would not be one of the most famous people in America. Ted played well enough for the forgotten Minneapolis Millers in the American Association to be promoted.

On April 29, 1939, at the age of 20, Ted Williams played his first game in historic Fenway Park in Boston, Massachusetts.

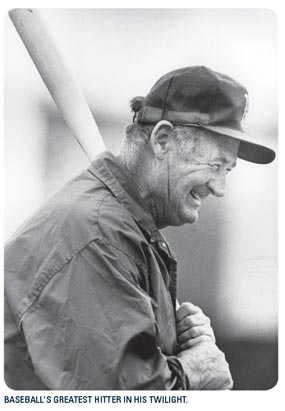

Over the next quarter century, Ted Williams would put together 21 Hall of Fame seasons. Those magnificent games were interrupted with four years of serving his country through two wars. He was a genuine All-American. As a boy, Ted told my dad and his friends in school that he wanted people to say he was the greatest hitter of all time. It all came true. Ted compiled a .344 batting average, had 521 home runs with 1,839 runs batted in. Also, while not known for being fast, he remains only one of three players to steal a base in four different decades.

Depression Boys

I recall one story told around our house demonstrating how tough things were near the end of the Depression and at the outbreak of World War II. After Ted signed his first big league contract, he bought a car and parked it in front of his parent’s house on Utah Street. Soon thereafter, the car was on jacks with the wheels stolen. His brother, who would lead a troubled life, yet was cared for and supported by Ted through a series of legal problems and health issues, a lifestyle leading to a premature death, had sold them for cash.

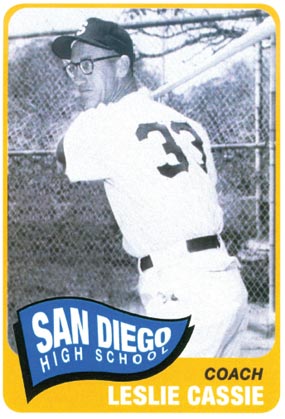

At the same time, his buddy, Les, long and lean and wearing his signature eyeglasses, entered San Diego State College. Baseball still mattered. He played on the baseball team and studied to be a teacher, a baseball coach and a sometimes scout. When the war broke out, his eyesight was so bad he was not aCCepted into the military. Instead, he took a break from his studies and went to work for the defense contractor that later became General Dynamics and labored as a draftsman building aircraft. Following the war, he joined a long line of soldiers and returned to SDSC.

Again, eligibility in place, my dad played ball. In the spring of 1945 or 1946, his San Diego State team was playing against UCLA in sparsely populated Westwood. It didn’t matter who won, but UCLA, like all the other schools, had an infielder who was getting started again after returning from the war. My dad pitched most of the game and gave up three hits to that Bruin without one of those balls getting out of the infield. The UCLA player was a multi-sports star by the name of Jack Roosevelt Robinson. Two years later, of course, the great Jackie Robinson would become one of baseball’s immortals and break the color barrier in the big leagues. He would also deservedly reach the hallowed Hall of Fame shrine in Cooperstown.

Ted brutalized American League pitching after the war and over the next five years led the league in every hitting category. The stresses of the real world intervened, however, in the form of the Korean War and on his way to re-writing the record books, Ted was recalled as a reservist after playing only six games in 1952. It is incredible to think of what his numbers would have been if Ted had not spent some key years of his career in a uniform other than baseball.

Ted brutalized American League pitching after the war and over the next five years led the league in every hitting category. The stresses of the real world intervened, however, in the form of the Korean War and on his way to re-writing the record books, Ted was recalled as a reservist after playing only six games in 1952. It is incredible to think of what his numbers would have been if Ted had not spent some key years of his career in a uniform other than baseball.

His war record has been well documented and his “ace status” as a pilot is a testament to his personal courage and his 20/10 eyesight. Williams said being a good pilot demanded athleticism. He taught others how to fly in WWII. He flew combat himself in Korea. Another big-leaguer, Yankee second baseman Jerry Coleman, was a pilot in a different squadron on a mission when Williams was shot down. Obviously, Ted survived. Coleman is the only major league player to face combat in both World War II and Korea. He would have a decent career as a player and spend more than twenty years as the announcer for the San Diego Padres. After flying 38 combat missions, Ted was released from duty and rejoined the Red Sox in mid-season, 1953. At that time, the Splendid Splinter was putting on the weight and muscle of his middle years. He was 34 years old.

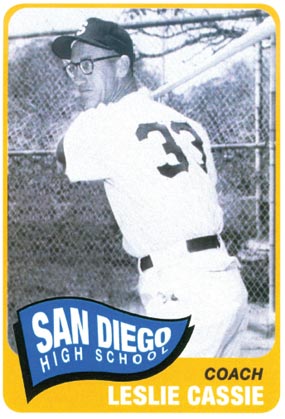

Coach

Throughout the late-forties and fifties, Les Cassie was a suCCessful coach at San Diego High School. Over 13 years, he produced tough teams that understood the fundamentals of the game. His coaching career included brief stints at his own Hoover High School and San Diego Junior College. His win-loss record was a staggering 200-28. He mentored gifted players, including Floyd Robinson who would play for the Chicago White Sox and Deron Johnson, who led the National League in runs batted-in (130) in 1965 with the Cincinnati Reds. Paul Runge, a fairly gifted catcher, played in the Houston organization but followed his dad as a major league umpire. Today, a third generation Runge is calling balls and strikes in the big leagues.

I recall coming home from the playground one day to learn that ‘The Thumper’ would be having dinner with us. My mother told me I couldn’t tell anyone Ted was there. If I had, she was concerned, aCCurately so, that the backyard would be filled with neighborhood kids. I remember the Russians had launched a satellite that day and we all were out there trying to see it. Ted had a rather salty vocabulary. No one used bad words in our house, so for me, it was like listening to the modern-day comics.

Ted always got around to talking about his favorite subject, hitting. In fact, the boy who left high school early wrote three books. One was called The Science of Hitting. He had charts and diagrams and it was something he understood viscerally and tried to share with others. I remember him asking me if the pitched ball looked like a “volleyball” coming at me. I said that it looked more like a “golf ball.” The next week I had glasses and have worn them ever since.

In 1957, my parents, my brother Tom, me and another couple, took a trip in a Buick Special. It was part business, but mostly pleasure. We spent three weeks in a car with no air conditioning visiting places like Joplin, MO, Chicago, Binghamton, NY, New York City, and any other place where there was someone in organized ball that my dad had played with or coached. The best stop was Boston. Ted always lived in a hotel. It was there I met Bobbi Jo, his daughter by his first marriage. She was my age, maybe a bit older. I remember we needed to run everywhere to avoid his fans. It was amazing. It was on this trip that I had my first ride in a taxi. Bobbi Jo was fearless and immediately got on the portable radio to talk with the dispatcher, who she seemed to know. She was something.

Ted loved the outdoors. He was allowed to keep his hunting skills sharp during the season by shooting pigeons that landed on the infield at Fenway. He did agree to do this on game day afternoons when the fans were not around. As gifted a fisherman as a baseball player, he lived in the Florida Keys during the off season. Sometime near the end of his career, a hurricane hit the Keys and many of the items he saved from his playing days were lost. I came home from school one day and there was a large trunk in the garage. It was filled with Ted’s old uniforms, hats, gloves, baseballs, bats and more. He had shipped what remained of his collection to our house. I recall thinking this is just a bunch of old stuff. I was wrong. Just before Ted was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1966, the trunk was shipped to Cooperstown.

Last

Ted’s last season was a memorable one. In 1960, at the age of 42, he hit .316 in 113 games. In his final trip to the plate, he hit one out. He touched home, ran in the dugout and went directly to the clubhouse. He later said he wished he had stepped out of the dugout and tipped his hat to the Bosox fans. His relationship with them was an uneasy one, but Tom Yawkey, owner of the team, respected Ted so much that in the latter part of Ted’s career Yawkey sent him a blank check with his contract and allowed Ted to fill in the number.

One of my last recollections of my dad with Ted was at a dinner in San Diego that was sponsored by Sears. Ted had signed a deal to put his name on fishing rods, reels, guns, baseball gloves and anything else that would help sell their merchandise. During the meal, the president of Sears asked Ted how he liked their new line of fishing gear. Ted abruptly said something to the effect that he just has his name on it, he doesn’t use it. It deflated the Sears man.

From 1969-1971, an aging and increasingly irascible Ted managed the Washington Senators and led them to their only winning season with that name and in that city. I remember visiting with him during a series with the California Angels. He was swarmed when he went through the hotel lobby, but he really didn’t want to stay in his room. We went to the ballpark. It was mid-afternoon and he asked the Angels to put a rocking chair in centerfield prior to the night game. Soon Jim Fregosi, the Angel star at the time, and several of the Angel players were talking about hitting with ‘The Kid.’ That night, the Senators beat California 2-1 in 15 innings. My wife at the time thought it lasted an eternity, and when asked by Ted how she liked the game, told him, “All you guys do is spit and scratch.” Imagine that.

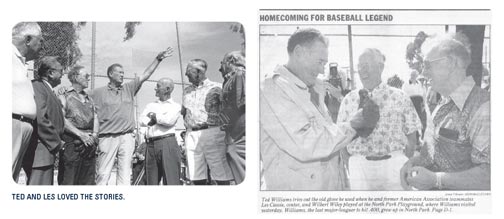

My dad and Ted talked over the years on the telephone. They did manage to get together for a mini-reunion at their old playground during a celebration in San Diego where they named a freeway after Ted. In 2000, Les would be inducted into the Coaching Legends at the San Diego Hall of Champions. Ted summed up their friendship. “You know,” he said, “I’ve always thought of Les as my brother.”

I was lucky. Les was my dad. Every time I went back to San Diego and someone heard my name they would ask me if Les Cassie was my dad. I’ve said yes a few times in my life. I’ve never said it with more pride than I would say it at those moments. I loved him very much.

The End

The end for Ted was unfortunately bizarre. Shortly after his death in 2002, his son, John-Henry, a product of his second marriage, produced a family pact that apparently Ted had signed saying he wanted to be “suspended by cryonics” at a life extension foundation in Scottsdale. Bobbi Jo, still tough like her dad, sued, saying her father wanted to be cremated. That was what Ted told my dad. He even added that he wanted to have his ashes scattered over the Florida Keys to join a favored, previously departed dog, Slugger.

The theory was that John-Henry was marketing his dad’s reputation and wanted to sell his DNA as a possible winner. At one point, my dad told John-Henry that “nobody has more of Ted’s DNA than you and it doesn’t help you hit a curve ball.” Ted’s boy would not enjoy the benefits of his marketing skills for long. He died from leukemia a few years after Ted, at the age of 35.

Les

My dad passed away in May of 2008. My mother joined him in October of that year. They are gone, but my brother and I were left with a locker room full of good memories. And this one is as good as any. On our trip in 1957, after visiting with Ted, we went with him to New York where they were playing the Yanks. My dad was a scout at the time for the Yankees, so Tom and I got to go into their clubhouse and see the likes of Bobby Richardson, Hank Bauer, Mickey Mantle, Moose Skowron, and Yogi Berra. There was also another San Diegan in the clubhouse – Don Larsen; the only man to pitch a perfect game in the World Series (1956). What a treat. Our seats that day were directly behind home plate in the first row. One inning, Ted led off and said something to the catcher, Yogi, who turned and gave a quick wave to a woman in a red dress. It was my mother and she nearly fainted.

I still picture the setting today: dinner on Austin Drive in San Diego with Ted at the table and Ted says to Tom and me, “Do you know what the most important thing about hitting is? Get a good pitch to hit.” And that’s pretty good advice for a lot of things in life.

Postscript: On an early spring evening in 2009, I had the opportunity to meet Don Larsen and his wife in Sacramento. We chatted about mutual acquaintances we shared because of my dad. Larsen had graduated from Pt. Loma High School in 1947. Of course, the story always takes a turn. In 1998, another Pt. Loma High alum, David Wells, pitched a perfect game in Yankee Stadium. And who was in the stands? Don Larsen.

California Conversations (CC): Did you ever spend any time with Ted Williams?

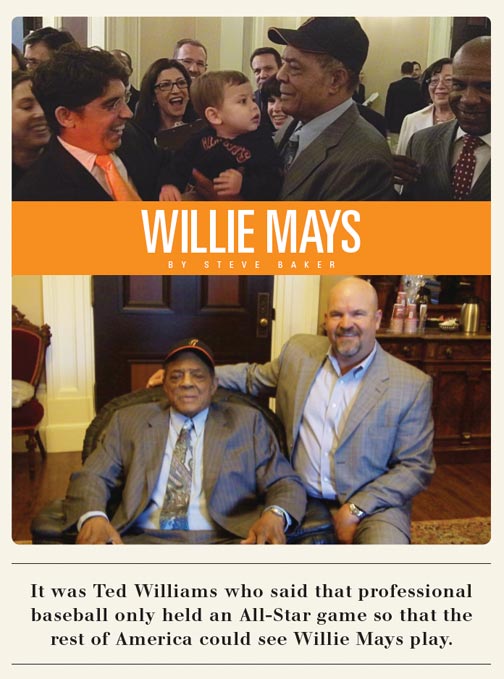

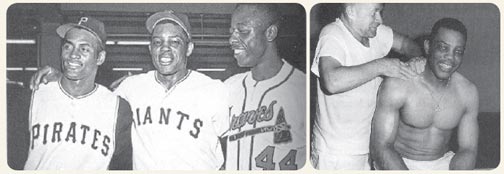

Willie Mays (WM): Ted was a good friend of mine. We would see each other at baseball events after we retired and he was always very friendly to me. And I guess that was not the case with everyone.

CC: Did you talk about hitting?

WM: No, I never talked hitting, or even talked about playing baseball, with Ted. I never really do when I’m talking to baseball people. Whatever anybody’s done, I’ve already done it.

CC: When did you first realize that you could hit the ball better than anyone else?

WM: I was 12. I didn’t play little league ball. I was already playing on a semi-pro team in my hometown near Birmingham, Alabama. I could hit the ball better than guys anywhere around my age, and I was playing with grown men. I was playing on teams with my dad.

CC: Your dad had a great nickname?

WM: Yes, he was called Cat Mays.

CC: Was he as good as the Say Hey Kid?

WM: I don’t know. (Laughs) I don’t judge. I don’t do that. I don’t judge people by what I do. I think the fans have to do that and not me.

CC: What was the biggest difference between playing in New York and San Francisco?

WM: Nothing. It’s just baseball. You catch the ball, you throw the ball, you hit the ball.

CC: Would the Dodgers and the Giants hang out when you all worked in the same city?

WM: No. When the game was over they went their way, I went my way.

CC: Did you live in New York City?

WM: Yes, I lived on A Street, right by La Guardia Airport and then I lived in New Rochelle on North Street. That was back in 1956-57. Then we moved to California in 1958 and San Francisco has been my home ever since. I like California.

CC: When you were in the Army, were you ever concerned that you would lose a step or that you wouldn’t be able to come back and play baseball?

WM: No, I really didn’t think about it. The Army was good for me. I grew up, I got stronger. I played five days for the Army and two for myself in a City League. I didn’t want to go. I made the best of it. I might have had another 60 or 70 homeruns if I hadn’t gone into the service.

CC: You would have broken Babe Ruth’s record?

WM: Yeah, but still that wasn’t important. It’s just a number to me. My father and I used to talk and we discussed that you have to be in the top five of everything important and if you look at my record you’ll see I’m in the top five of stolen bases, hits, knocked-in runs, home runs, all kinds of stuff. Top five. Think about that. A lot of guys are good hitters or good fielders, they’re good base runners, but they’re not in the top five of many things, maybe just one thing. I played 150 games or more for 18 or 19 years, and that, to me, is a lot of games. I led the league in stolen bases four years in a row and then I quit running. I only stole when I had to.

CC: 338 stolen bases?

WM: I could have stolen 450, probably 500 if I wanted to. Again, those are just numbers. They didn’t tell me they were going to keep records on that kind of stuff.

CC: Can you teach hitting or do you just have to have that skill?

WM: I can tell someone what to do and how to do it. We had a kid, a third baseman, Matt Williams, and Matt couldn’t hit a breaking ball when we first got him. We taught him.

CC: When people talk about the great hitters…

WM: Hitting? That is only one aspect of the game. It’s not all about hitting. I’d rather play defense than hit.

CC: Was defense more fun?

WM: It is the key to playing baseball. If you can play good defense and you can score one run then they got to score two. You see a lot of teams with good offense, but the offense is not enough.

CC: You won twelve gold gloves.

WM: They didn’t start that award until I was in the league for five or six years. I was the captain on the field and I would set our team up depending on where the pitcher was going to pitch. If he throws the ball in the same area and you know the batter, you will have an idea of where he is going to hit it. The great catch most of the time is not having to make a great catch. It is being where you are supposed to be. Like people have computers now, I was computing in my head. I had to know everything about every club, every hitter.

CC: Who chooses the captain?

WM: On the Giants, the manager did. Alvin Dark did that for me. We played together when he was a shortstop in New York and if the pitcher was throwing a breaking ball, Alvin put his hands behind him to let me know it was coming so I could expect to catch a ball in the gap. He was good.

CC: When you are at the plate what does the ball look like when it is coming toward you?

WM: I could see the seams on the ball. Maybe that’s why my eyes are bad now because I had to squint to see what was coming all the time. I could see it all.

CC: You’ve said the famous Vic Wertz’ over-the-shoulder World Series catch was not your greatest catch.

WM: I made a lot of better catches than that, but it was the most publicized one. In 1954, the World Series was done in four games so they had to pick a highlight I guess and they picked that one.

CC: What would you have done if you had not been a baseball player?

WM: I don’t think I wanted to do anything else. My dad would never let me go in a coal mine, he never let me work, I never had a job. I actually had a job for 3 hours one day and I quit it because it interfered with my game.

CC: What was the job?

WM: Washing dishes at a restaurant. It was not a career I wanted.

CC: I hear you are a pretty good golfer?

WM: That was after baseball. I got down to 4 when I could play every day.

CC: Do people still come up to you and say “Bye, Bye Baby?”

WM: No (laughs). That was Russ Hodges. He was a great guy and a great announcer. They play ‘Bye Bye Baby’ at the ballpark now. I had two batting coaches, Lon Simmons, the other announcer, and Russ Hodges. They could see me changing my swing and they’d call me and say you changed and I’d go home and look at a film and find out they were telling me the truth.

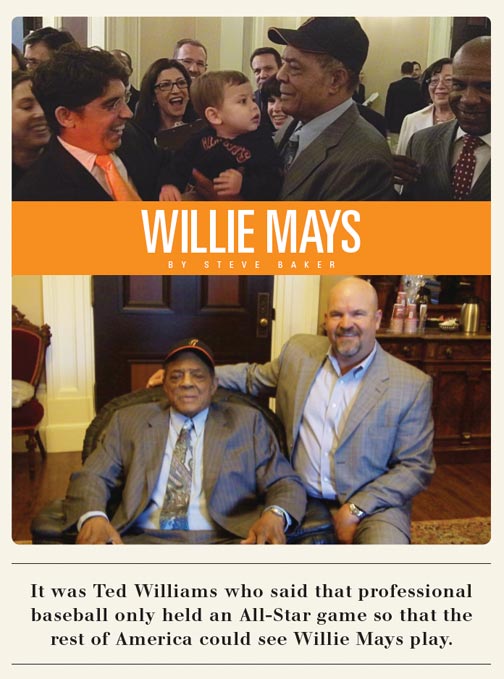

CC: The President pro Tempore of the Senate, Darrell Steinberg and the Speaker of the Assembly, John Perez, wrote a resolution calling you the greatest baseball player of all time and they presented the resolution to you on the floors of both their houses on your 79th birthday.

WM: It was a great honor, one of the great honors of my life. I was very proud to be there. (Laughs) And they got the resolution right.

CC: Can you help me get tickets to the Giants?

WM: (laughs) Call me. I can work something out.

But The Thing Will Still Remain

Terence McHale

Published Issue: Summer 2011

The Old Man

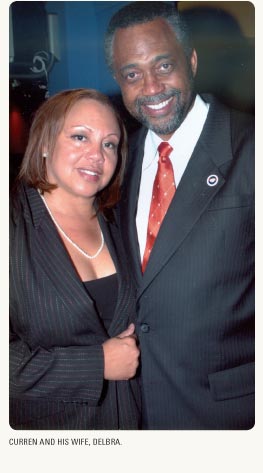

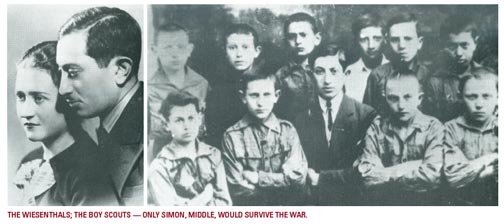

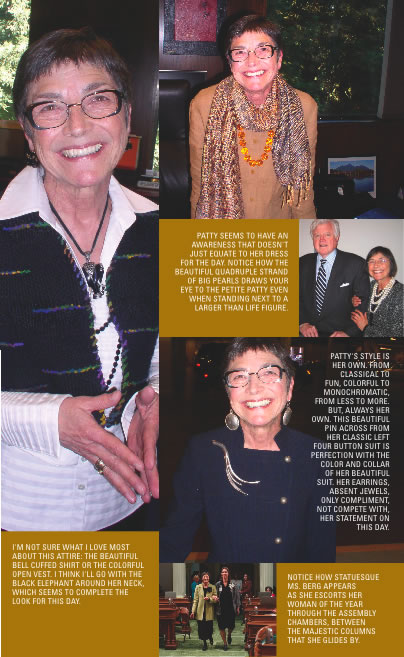

The picture was taken twenty or so years ago at a fundraiser. My friend, Cliff Berg, and his wife Debbie are in the photo. The third person is an old man. His features are drawn long, and his dark eyes are damp. His complex face is weighted down by experiences that never leave him. He has become a celebrity of sorts for the oddest of reasons. The old man survived the Final Solution, a twentieth century idea of inexplicable evil, a plan created to kill all of the Jews in Europe.

The old man lived long enough to cast a bright light on those who participated in the implementation of the Final Solution. His idea wasn’t complicated. He wanted everyone to know that decent people were dragged into a hell where every part of their lives was shattered before six million of them were killed. The old man wanted everyone to understand that their neighbors bought into a society where families could be violently removed from their homes. He wanted everyone to remember that families were stripped of their possessions and sent on trains to terrible places where they were separated by everyday bureaucrats with the authority over life and death. And he wanted those who were responsible to be held accountable for their crimes.

Rabbi Meyer May, an interesting man, explained that this old man would identify officers and guards at the camps who had killed people. The old man would say that it was murder, it wasn’t war. “War is when you are on the beach at Normandy and you’re being shot at and you shoot somebody else, that’s not called murder,” May said. “That’s called war, because that is the nature of war. What we’re talking about here is murder…about people being herded into a ravine and shot. We are talking about guards beating people to death, or hanging them, or forcing them into gas chambers. We cannot accept that there is a scale to murder. There is not something that says genocide and big murder are bad, but little murder is okay.”

After the war ended, the old man’s goal of telling the truth should have been an easy task. It wasn’t. No one wanted to disturb a fragile re-piecing together of a new world order. It was easier to say those times, the years of chaos that made up an era of war, the trips on the train while the rest of the world was bleeding, were an anomaly and needed to be forgotten.

The early days of what ultimately became the old man’s life’s work were solitary. He strung nickels together to finance chasing down soldiers and employees who handled the logistics of murder being managed on a massive scale. He worked by himself. It would have been much easier to quit and disappear into the quiet comfort of a private life. “You are becoming a lightening rod,” he was warned. He kept moving inexorably forward. He had seen too much to let those who were gone be forgotten.

This old man lived a life that was unimaginably different from what his parents could have hoped when he was born early in the last century, in a city that is gone, in a country that no longer exists.

Young once, only for a short time, even a bit of a dandy in the way he dressed and slicked back his hair; he wanted to be an architect. He was denied admission to the university of his choice because of his faith. It was not the first limit imposed upon him. He’d been beaten by soldiers when he was a child. There was no recourse. The soldiers had free rein to be as abusive as they wanted to be. It was an entitlement too many found too easy to indulge. The old man and those he loved were forced to wear a distinguishing symbol. The pogroms in memory were still real and new ones were now more inevitable than considered possible. The legal structure promised in Mein Kampf, and left unchallenged until it was too late, subjected him to fearsome abuses.

The old man’s talent survives him in drawings that are archived, and, had the tenor of his life been different, his artistic abilities were what would have made him noticeable. He fell in love and married his high school sweetheart. That is not a distinction that separates him from millions. It was the way he would prove himself resilient that makes a difference. He was old in the picture with Cliff and Debbie. He got old fast and was old for a long time.

In 1938, a popular short plug shown before the American movies warned the world of the continuing horrors emanating from Germany. The old man in the picture knew of them. He was the hunted in an age of systemic anti-Semitism. By 1939, in a civilized part of Europe, in a modern world, it became illegal for him to drive a car or own property. It was socially acceptable to do much more than break his windows or destroy his business, or beat him up and make anathema the manner of his worship. The Nazi evil – ugly, perverse in retrospect and monumental in history, a marketing and political movement that swept away common decency – permeated a continent. The brown boots and the strutting, the magnificently staged rallies, the hysteria, the Arian purity espoused by weakling men, an absurdity that is now so easily caricatured, were capped by a nationalized stiff-armed devotion to a demagogue with absolute power.

The old man in the picture understood that political extremism sold an imponderable cruelty. Adolf Hitler put the world at war on the premise that a future could be built on a personal violence against Jews. He empowered the sycophantic son of a school principal, a harpsichord player named Himmler, to lead the design of the Final Solution. Adolf Eichmann, a door-to-door salesman with organizational skills and, even by the old man’s estimation, someone who lived the life of a family man, made the trains to hell run on time. The old man would play a role in the capture of Eichmann after the war and would note that this common man’s trial would only have made sense to the prosecutors if he pled guilty to murder six million times.

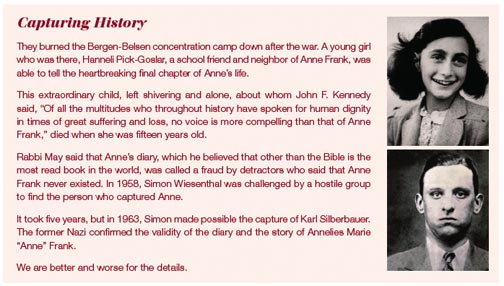

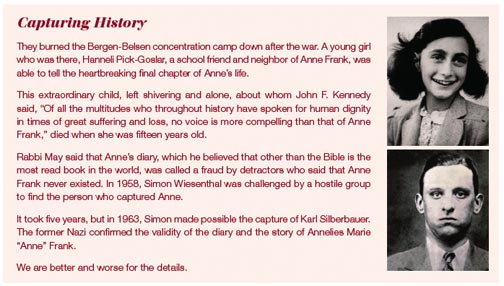

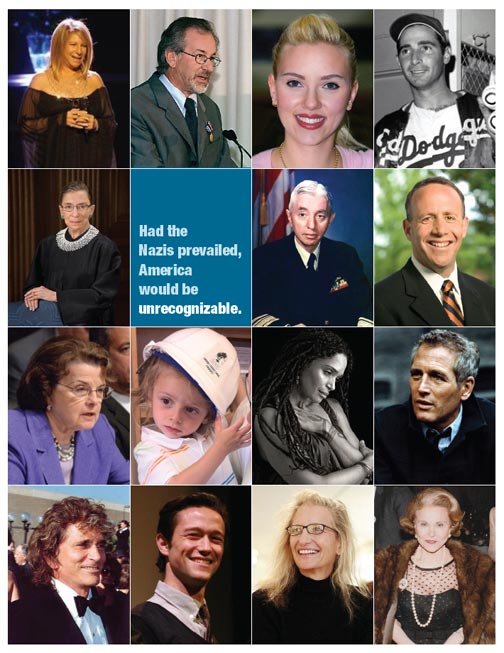

The consequences of a Nazi philosophy can be explained a generation later in gut-wrenching newsreels of a devastated Europe and in the longings of a young girl’s diary. The bombed-out buildings provide a ghostly silhouette. The naked bodies piled in a heap challenge our humanity. The disappearance of Anne Frank resonates throughout the years she deserved to live. She would be an eighty-two-year-old grandmother if there’d never been people, everyday people, neighbors, storekeepers, salesmen, classmates, clerics, harpsichord players hoping to be athletes, who believed in Hitler.

This old man in the picture endured years of captivity. He was brilliant and ambitious and he’d committed no crime.

He was six feet tall, lean, well-built and healthy when the nightmares took over. At the end of the ordeal, and that is all the Allies and the enemies wanted to call the murder of six million people, he weighed only 110 pounds. That is bones. That isn’t being hungry. That is starvation. That is being sent from bunkhouse to bunkhouse where individual Nazis are given the freedom to reduce you until they decide to kill you. He was left in the control of people who worked as plumbers, steelworkers, clerks, and teachers before the war and would try returning to that normalcy when it ended. At one of these insulated camps, the same people who tormented the prisoners as a matter of course constructed a chapel that was visible on the pathway leading to the gas chambers. What benevolent and merciful god did they kneel to in those years? Was it the same god they worshipped before the war and then found waiting for them after they no longer had badges and whips?

The old man was sent to a series of concentration camps, thirteen of them, extermination camps, places of slave labor and everyday humiliations. He lived with execution as a constant threat. Among the millions who would die in a celebrated system of slaughter would be 80 family members of the old man and his wife. He endured the endless deadly minutes of the implementation of a Final Solution that took years to ultimately fail.

The old man would live long enough to chase those who managed to weave murder into public policy.

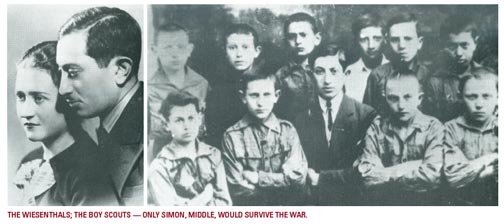

There is an ancient photo of the old man as a leader of ten other boy scouts. He is the only one who survived the Nazis. The youth before the Nazis took hold of him is completely gone. The young man that once must have charmed and inspired is unrecognizable in an old man who refuses to forget. Where was home he wrote when the war was over? What did the concept mean? What remained of family, friends, a house, relations? None of these existed for him any longer. In the picture with Cliff and Debbie, the old man’s mustache is turning white. His high-domed forehead is a less noticeable feature than the deep folds around his thin hard-set lips.

Everyone at the fundraiser with Cliff and Debbie was there to meet the old man. He survived the wholesale killings. He delineated the difference between vengeance and justice and dared to say, against incredible opposition, that there is a consequence when employees or soldiers turn into monsters. Incredibly, after all it meant for him to be a Jew, a man whose mother died in a gas chamber and whose mother-in-law was shot on a porch in her old age, and the girl he loved was lost for years in the Nazi labyrinth, there was a museum of tolerance being built in his name.

Six million Jews died. He knew them. In his lifetime he also made a point of remembering the gypsies and the homosexuals and the disabled and the noisy, although infrequently heard, political opposition who died because they didn’t fit an Aryan ideal. The Final Solution swept others into the net. He understood what all of them endured. He knew. It is impossible to think about what kept him awake when he went to bed at night.

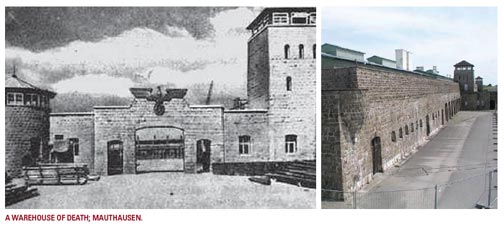

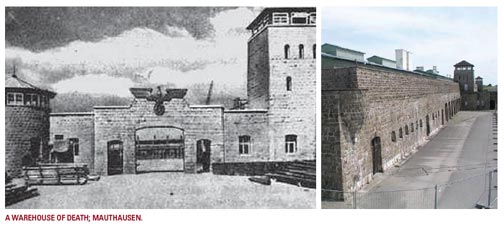

The old man awakened on the 5th of May, 1945, in the Mauthausen concentration camp and greeted the tanks that arrived to liberate the prisoners. It is almost ridiculous to call it a camp. There were 85,000 inmates. Two hundred twenty thousand people died in that tortuous hellhole since it was opened to handle the overflow from the first concentration camp, Dachau, seven years earlier. Can anyone say Dachau now without wondering what was the gossip at the neighborhood market? Who is living in the Berg house? What does a person give up inside to know that Dachau is at the corner?

On the morning that the Allies arrived the old man was punched by a clerk who thought the consistent brutality would continue. It wouldn’t. By the second morning, the lines of power had shifted. The strutting Nazis were reduced. They were emptied of their starched uniforms. They were void of the power over life and death to which they had grown accustomed. The commandant was already on the run. He would die within days and have his body hung on a fence in an ignominious display. Himmler, the harpsichord player turned Halloween architect, would try cutting a deal and find there were no takers. Suicide was his option. Eichmann was running too. The old man would find him.

The old man began a list of the war crimes he had seen the Nazis commit in the camps. He was meticulous. He spent twenty or so days compiling the list in Polish. He was an ill, skinny ghost in a striped uniform summoning testimony from those who lost the grim grasp on the life he still owned. He knew their voice was silenced and he was going to make sure they were heard. The list was done on different pieces of paper for each camp where he lived, and struggled to survive, and the ninety-one Nazis he named became the beginning of his life’s work by letting their crimes be seen in the light. It was important enough of a document that the Allied investigators would save it for evidence. That list still survives today. In the end, the old man would become the Nazi hunter who made justice, not vengeance, his legacy.

The old man is wearing a name tag in the picture with Cliff and Debbie.

Now, long after the villains of that generation have been mostly filed away in a shameful chapter, his name still matters.

The name is Simon Wiesenthal.

Museum

The Museum of Tolerance is an ultra-sleek multimedia, hands-on educational arm of the Simon Weisenthal Center on busy Pico Boulevard in Los Angeles. Busses pull up with kids who like the idea of a field trip. There is the timeless delight of school children out of the classroom and on a break. They are not unlike lines of other kids who are about to enter an amusement park. Maybe they’ve been told that this Museum is not out to entertain them. It doesn’t matter. Until they get inside there is no way to prepare them for their encounter with an age that preceded them.

They are greeted with framed photos of elderly survivors decades removed from captivity. They look like people we’ve always known, our neighbors, our friends, our family, and yet once they were targeted. Underneath their photos are the places they were incarcerated. It is not yet clear that there were almost 1,500 camps, some in Germany, most in occupied countries, some of the names familiar, Bergen-Belsen, where Anne died, Ravensbruk, Konin, Auschwitz where more Jews died than all of Britain lost in the war. In Austria, at the turn of the century, there were more than 240,000 Jews. In 1945, there were less than fifty. There are quotes chosen by the former prisoners of the Nazis; “When I needed to survive, I did.” “Hate is a waste of time.” “Indifference let hatred rule the world, and six million people died.” “My parents never saw their only child grow up.”

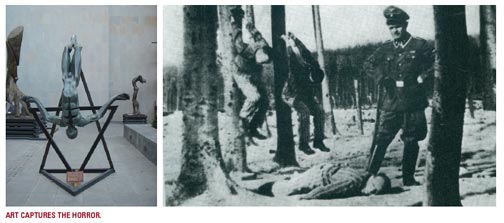

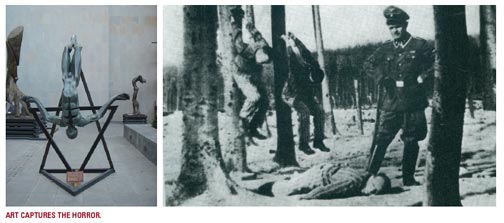

A sculpture, Holocausto, by Jose Sacal, is reminiscent of the way Jews were hanged in the camps. In 1979, Wiesenthal used an actual photo of such an image on postcards that he sent to the German Chancellor asking him to extend the statute of limitations on Nazi crimes. The photo was a stark view of the ease with which torture and murder were part of daily life in the camps. The sculpture conveys what one in six million looks like.

The museum was designed by storytellers. The implementation is high-tech, modern, and hands-on, keeping your attention as you move past screens that challenge you with the power of images and words, to a millennium machine where the seriousness of the field trip is instantly clear in the questions of morality and conscience that are asked and computed. Each of the visitors to the Museum is given the identification of a person who was arrested by the Nazis. It sets the stage for a journey that becomes more personal as you experience all the attendant horrors associated with genocide. It is haunting. There are the personal items that survived. The relics from sacred places are preserved but no longer protected by those families who found peace and hope in the items. You learn about a community, the dancing, the dreams, the worshipping, and then discover it no longer exists. You learn there are many communities that no longer exist. There is the constant foreboding of being chased by the powerful.

You walk through the brick entrance of a concentration camp. It would be trite and unfair to say you get anything close to the same experience of those who were there when such a walk into madness made up real life. It is, however, a vivid moment and the groups of kids who were celebratory outside are now quiet, involved, clearly trying to make sense out of the hatred. Some kids cling to each other. There are tears and there is a wondering how it happened.

Perhaps most powerful is the message that this incredible history would have been impossible if average people did not allow it to happen.

Rabbi May explained that Simon believed the world is made up of haters and anti-haters. “My greatest memory of Simon is when he had just come back from speaking to students. He wanted kids to know that they had a stake in the world, and it is up to them to make the right choices. It is up to you. It isn’t up to anyone else. Every person has to walk out of the museum thinking it is up to me.”

Meyer May

The offices accommodating the work of the Center are across the street in a nondescript building with underground parking. There is the concomitant security that is unfortunately inherent with running a Jewish Center. More than a half-century after the war, the prejudices survive.

The young man who checked my rental car asked who I was there to see. I said I had an appointment with Rabbi Meyer May. He was the first of several employees who told me, unsolicited, how the Rabbi was special to them. An older guide at the museum tapped his chest when I mentioned the Rabbi and said that Rabbi May was in his heart. A woman mentioned how the Rabbi personally cares about everyone who works at the Center. He is a mensch, she said, sure I would know what that meant and happy to convey some good news.

The Rabbi’s office could just as easily belong to a college professor as it could to the CEO of a good-sized company. There are no pictures of the many celebrities he has met over the years, and while there are books, there was nothing pretentious about his collection. I did notice that at the top of a stack on the floor was a private coffee table copy of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s heroic presentation of his years as governor.

The Rabbi is probably in his fifties. He has four lines in his forehead, none of them deep, and he is neither wrinkled nor compromised by middle age. He is nice looking, with hair that is lighter-colored than when he was younger, now gray and balding, and he clearly benefits from his daily walks and clean living. His beard is trimmed, stylish maybe in Rabbinical circles, and also showing the gray. He is friendly, not reserved and not the life of the party, a kindness, immediately good company, a great smile, and a New York accent that has been softened over the years. There is vitality to his movements, intellectual for sure, but more than that; an energy, an enthusiasm that is evident even when he sits behind the desk.

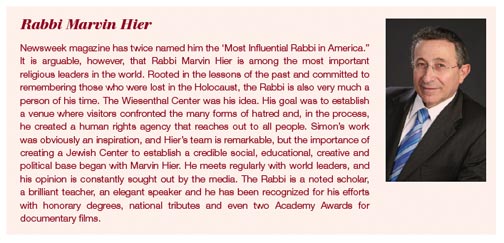

He speaks highly of his more famous colleague, the eminent Rabbi Marvin Hier, the founding dean of the Wiesenthal Center. He gives others credit for the Nazi hunting. Rabbi May is involved in the financing of the center. The Rabbi is officially the Executive Director, a member of a team that has brought more than five million visitors into a museum that seeks to establish a baseline for tolerance through educational outreach, community involvement and social action.

Meyer May was there when the Simon Wiesenthal Center began. He was a young man when he met Simon.

“I knew him when he was a robust person,” May says. “I would pick Simon up at the airport and drive him wherever he needed to go. In those days we didn’t have cell phones. We weren’t texting. We would often eat together. He liked telling stories and had a great sense of humor, sometimes a profane humor. Simon was interesting and would talk of world events. He would talk about cases that had gone wrong, and cases he was working on. He would talk about Israel. His wife asked him why they didn’t move to Israel, why he kept his office in Vienna, and he said the Nazis were not in Israel.

“It is often forgotten that until the Wiesenthal Center started in 1977, Simon was working, literally, by himself. People just didn’t want to be involved with this. At one point he tried to raise five hundred dollars and couldn’t do it. People would say, I’ve been through it, and I want to forget it. That’s why survivors never talked about it for a long time, and from 1945 until 1977, 32 years, Simon worked by himself.

“Simon was not at peace with God after the war. I asked him why. He said, ‘I’ll tell you why. When I was in the Holocaust there was a man who hid a Siddur, a Jewish prayer book. He had a prayer book with him and everybody who wanted to use it had to give some of their rations to this person. I saw someone trade his Siddur for rations that were so meager and necessary. I was disgusted. I said I’m never going to pray again.’ It was a forcefully told story. However, in telling it, Simon also took pause and willingly acknowledged the people who were willing to give up their rations in order to pray.

“Simon lived in places where you see all sides of people.”

Simon

In his own words, in his book, Justice, not Vengeance, Wiesenthal describes the final day of his visit to Israel in January of 1964. He explains that on each trip to Israel he tried to come home with new names of Nazi war criminals that were given to him by Holocaust survivors. On this particular day, three Polish women asked him if he knew what happened to Kobyla.

Wiesenthal explains that “kobyla” is the Polish word for “mare”. The three women explained that there was a female Nazi guard in their women’s concentration camp, at Majdanek, who was given the nickname “mare” because she was always kicking the women prisoners. She was known for carrying a whip that she used to lash and humiliate the Jews left in her charge.

This Kobyla, whose real name was Hermine Braunsteiner, seemed to take particular joy in choosing extra prisoners for the gas chambers. There are stories of her ripping children from their mothers and throwing them up on the back of a wagon.

Wiesenthal spoke often of individuals like Hermine Braunsteiner, a person who would otherwise probably never murder anyone, uncovering their latent sadistic inclinations in concentration camps. They were able to fling a child through the air like a sack of potatoes, strike young girls across the eyes with whips, beat those already weakened by starvation, or fire a bullet into a person’s face.

The Mare

Wiesenthal decided to find Braunsteiner.

He discovered that her family lived in Vienna. He learned that Braunsteiner came from a strict Catholic family and that as a little girl she always dressed up for Mass. The neighbors explained that the family was not wealthy. Her first job was as a maid. Hermine had gone to work as a prison warden during the war. She accepted higher paying jobs at the camps and was awarded a medal for her efficiency. Immediately after the war, there was a tepid effort to deal with the base inhumanity of particularly notorious Nazis. The Mare would spend three years in prison. It was a sentence that she was able to hide from an American serviceman named Ryan. She married him and moved to the United States.

He discovered that her family lived in Vienna. He learned that Braunsteiner came from a strict Catholic family and that as a little girl she always dressed up for Mass. The neighbors explained that the family was not wealthy. Her first job was as a maid. Hermine had gone to work as a prison warden during the war. She accepted higher paying jobs at the camps and was awarded a medal for her efficiency. Immediately after the war, there was a tepid effort to deal with the base inhumanity of particularly notorious Nazis. The Mare would spend three years in prison. It was a sentence that she was able to hide from an American serviceman named Ryan. She married him and moved to the United States.

“During the nineteen years since the war ended there had not been a single Nazi war crimes trial in the USA, and no one had been extradited to another country for such crimes,” Wiesenthal wrote. He thought this legal case looked favorable because if Braunsteiner did not mention her previous conviction to immigration, then there was a legitimate reason to revoke her U.S. citizenship. He hoped a trial would be imminent.

Wiesenthal contacted the Vienna correspondent of the New York Times with information that Hermine Braunsteiner might be living under the name Hermine Ryan in New York City.

New York

In the spring of 1964, there was no such thing as the Holocaust. That name was not yet commonly applied to the openly acceptable Nazi terror against Jews. The Final Solution was considered an anomaly of war. No one was paying attention. The killing of six million ignored the indignities and actual murder of each person in the accumulation of the ghastly number. Even in a country that prosecuted Andersonville, the Confederate prison camp at the conclusion of the Civil War, and hanged the commandant for his crimes against humanity, there was more than reluctance to address Nazi crimes among people living in the United States…there was a refusal. Until Simon Wiesenthal shined his light on Braunsteiner, who was married to an American and living as an American, there had been no prosecution of any Nazi who found refuge i the United States.

Of course this sanguine approach to bloody, cold, muddy brutality was not solely an American sin. There was a point when Wiesenthal couldn’t raise five hundred dollars to search for the Auschwitz doctor who wallowed in depravity, the quintessential Nazi, Mengele, whose last name is such an abomination for his experiments on the most vulnerable, that merely saying it conjures something nightmarish in the way humans can behave.

The assignment to find the brutal Mare, Hermine Braunsteiner Ryan, was given to a rookie reporter at the New York Times by the name of Joseph Lelyveld.

Lelyveld wrote about Wiesenthal and the Mare in a book he called a memory loop, Omaha Blues, in 2005. Forty-six years after he went looking for Braunsteiner, we spoke to Lelyveld, who is now retired after a distinguished career with the New York Times.

“I was a very green reporter,” said Lelyveld. “I was preoccupied in how you do such a thing like finding Hermine Ryan and get her story. I thought it would be immensely difficult, so I wasn’t really worried about her. I was just worried about the reportorial part of tracking her down.

“It was easy, and if I had been more experienced I would have understood that it was easy to begin with. Being an Austrian, she would stand out in the predominantly Irish community in New York. Unless she had hidden out, people would have been aware of her existence.

“I can still imagine what she looked like and what she sounded like. But a clear memory…this is the funny thing about memories; I had a pretty clear memory of the whole conversation and her appearance. Then not that long ago when I went back to my original article, some of what was in my memory was not supported by the article. Especially my memory that when she answered the door, she said, ‘You’ve come.’

“As inexperienced as I was, I can’t believe that if she had actually said that I wouldn’t have used it in my article. Then in my article she was described as wearing shorts and a matching top and holding a paintbrush. I remember the shorts but I didn’t remember that there was a matching top and in my memory it was a feather duster she was holding.

“There was nothing frightening about her. If you had passed her on the street you wouldn’t have seen anything frightening in her. That, I guess, is the whole horror of the Holocaust; perfectly ordinary people turning into psychopathic killers.

“I know nothing about her origins. She was very young when it happened. She wasn’t so old when I met her. To me, the war seemed a long time ago at that point but it was less than 20 years before. I imagine she was in her early 40s when I encountered her.

“The assignment came to us from Vienna, and the story of Hermine Ryan had been passed on to us through the word that Simon Wiesenthal had knowledge of her whereabouts. It was an extraordinary experience, but I don’t believe it was any personal achievement on my part. It just fell to me as an ordinary matter of a newspaper assignment. It wasn’t a great feat of reporting for me to have found her. It’s nothing I feel proud about. It’s just one of those amazing things that can happen to a journalist in the course of a day.

“I do know that I wrote in my own book and in my own memory of the occasion something to the effect that even by the standards of extreme cruelty in those days, Hermine Braunsteiner Ryan went beyond it in her ferocity. According to some of the materials I found during my later research, and I’ve never looked at the transcripts of her trial, that does seem to be the case. She seems to have done some monstrous things, which raises an interesting moral question about whether there is any redemption for a person who does monstrous things.

“My father was a rabbi, and I don’t have any easy answer for that kind of question. I do believe it was good that she was extradited from the United States and convicted in a German court and that she served time in Germany. Of course, there is no justice in these matters. There can never be any justice. I know their efforts continue to find the last 85-year-old killer and to reclaim some piece of property for families that were almost wiped out by the Nazis. It’s so hard to disapprove of those things, but they seem so paltry in comparison to the wicked deeds that were done, that they are just footnotes.

“There is no such thing as restitution in regards to the Holocaust. There is just a playing out of the story, and one day very soon there will be no further playing out of the story because there will be nobody left alive who was directly involved.

“But the thing will still remain.”

The Thing Still Remains

It would take nine years to extradite Braunsteiner. During her trial, which she shared with fifteen other Nazis, one of the longest trials in history, witnesses would tell of the vicious beatings and how the woman who tried hiding as a housewife in America, kicked inmates to death with her steel-toed boots. She would be found guilty of murdering and collaborating in the murders of more than 1,000 people, including 102 children. The testimony in a sterile courtroom of her throwing children by their hair onto trucks was the detail of real moments for the women put in her charge. The stories of her cruelty make you wonder what died inside the Nazis that allowed them to make such behavior a matter of course. Braunsteiner would be sentenced to prison on June 30, 1981, four decades after her crimes were committed. She would receive the mercy she denied others when she was released for health reasons fifteen years later. She died a free woman at the age of 79.

Simon Wiesenthal’s greatest fear was that ‘the monotony of horror’ would become too much for people to take in, and possibly even emotionally digest. Simon wrote, “Sometimes I am seized by the fear that teachers and children in history lessons will be saying in the 20th Century Hitler tried to set up a great empire in Europe. Contemporary witnesses maintained that he had attempted to exterminate the Jews of Europe. There is talk of the poisoning of Jews in specially established camps. It seems excesses were in fact committed, though those accounts are probably greatly exaggerated.

“We are under an obligation,” he continued, “to make young people realize how unique, how unbelievable, how exceptional the period of the Holocaust was. By this very attempt, we make it difficult for them to accept our accounts as the truth and as facts. The incomprehensible remains incomprehensible.”

There is no way for reasonable people to understand an ideal that would legalize and promote the imprisonment and murder of millions of people. How do we make sense of the individual actions that ended the life of a beautiful young girl and countless like her, the unrestricted brutality visited on neighbors, depraved conditions that were part of a master plan, a final solution, a visit by a Nazi officer that was celebrated with the shooting of hundreds of Jews. How do any of those who participated ever find their soul again?

The reporter, Joseph Lelyveld, struggled with the idea of redemption. Rabbi May said, “In Judaism we call it repentance. A person can repent. They can repent up until he or she dies. But does Eichmann ever have an opportunity to repent? Does a mass murderer have an opportunity to repent? Does a small murderer have a chance to repent? It is a difficult thing which would require an extraordinary, serious commitment by the person to change their life. But only G-d has the ability to accept the penitence and to know the penitent’s true remorse.”

The Rabbi took a call from his daughter-in-law at the conclusion of our meeting. He asked her if his grandson was playing basketball and if he had his guitar. He smiled broadly when his grandson got on the phone. He said to the little boy, “I love you. I love you like Craisins.”

In Hitler’s world, and the world of the average men and women who followed him, the Rabbi would be gone.

Simon

Simon lived a long life. He died at the age of 96 on September 20, 2005, in Vienna.

“I don’t think Simon ever became a person who prayed three times a day,” said Rabbi May. “He did not keep Kosher, but he had a connection to Judaism. He was buried in Israel. He wasn’t cremated. He was buried according to Jewish law. So, no hanky-panky. No short cuts. I don’t think he was angry at God by the time he died.”

In the picture with my friend Cliff and his wife Debbie the old man who had done so much is wearing a name tag.

There is a remarkable museum that bears his name. And those he wanted remembered will never be forgotten.

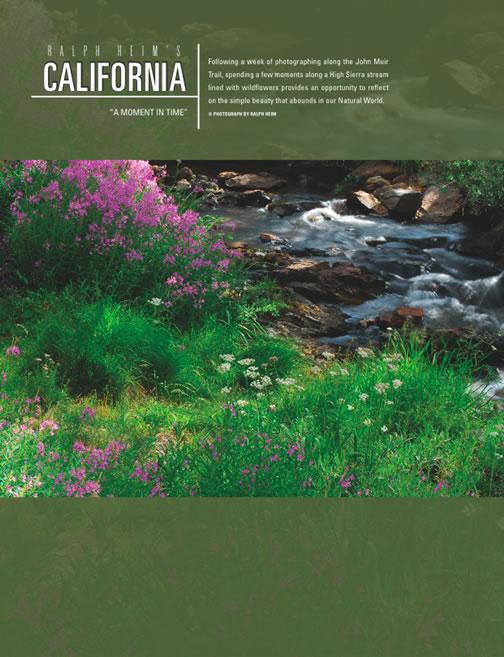

A Long Hike in a Historic Place

Adriana Calderon

Published Issue: Summer 2011

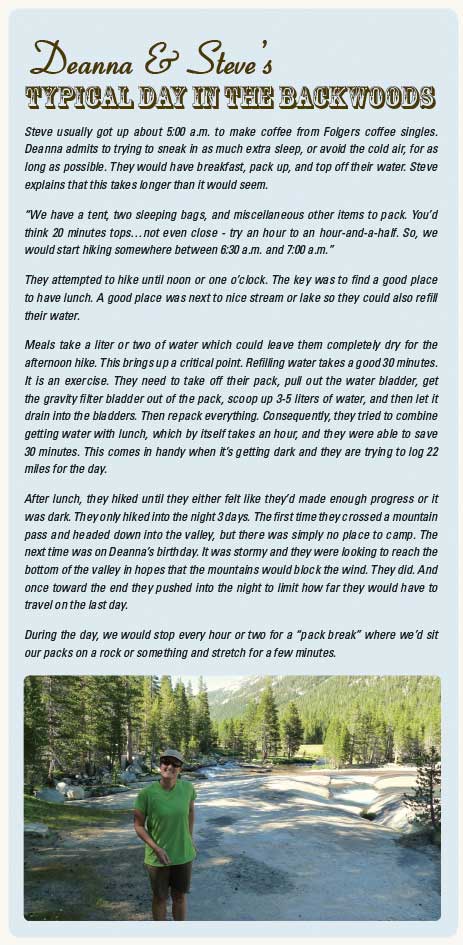

Deanna and Steve met at the Tahoe Rim Trail Endurance Run. He was running fifty miles and she was doing the 10K, a 6.2 mile run.

Deanna finished with her run first and left a note on the windshield of his car asking him to call her and let her know how the run went for him. He still has that note. They ended up with each other and it is an enviable match.

You can hear it in their voices that they know how lucky they are to have found one another. He’s an emphatic military guy who once spent seven months in a submarine and when he mentions his wife there is a lightness and humor. She doesn’t last very long in a conversation without finding a reason to laugh. She is serious when she says the best part of being in the wilderness is Steve’s company.

100 Mile Runs

They did their first 100 mile run together in Arizona. It took 27 hours. There was no sleep and 96 miles into that Arizona run Deanna said she almost quit.

“Steve was like, ‘What? You’re kidding me right’?”

Deanna has a laugh that is close to crystal in its clarity. It is completely natural, and when she tells a story it punctuates the image with a sense that she is taking you to that moment.

“I just had to sit down. I sat on a rock where you could see in the distance the end of the run. That is not what got me started again. I also saw a snake hole right next to me. That got me off the rock.”

Deanna and Steve made a habit of endurance runs. Deanna who started running for fun when she was twenty-seven, doesn’t flinch when she talks about events such as the Western States 100 mile event. They have run countless marathons. For added fun, they hiked Point Reyes at 13-15 miles a day, and the Pacific Crest Trail near Donner for a quick 27 mile overnight hike.

“I don’t know exactly what draws us to the long runs and physical challenges. It is a good question. I think it’s just to see what we can do and how comfortable or uncomfortable it will be.”

Friends told them of the John Muir Trail and the unbelievable beauty. They were shown pictures. It became something they wanted to do, not sure really what to expect because they had never gone backpacking for more than five days at a time. They’d never done the kind of backpacking where you spend eleven days in the back country.

The John Muir Trail

John Muir died on Christmas Eve, 1914. It was a monumental life, one of remarkable achievement, including the protection of some of California’s most precious natural resources, the founding of the Sierra Club, numerous books and essays that inspired following generations of environmentalists, and even the despairing loss of Hetch Hetchy to a dam.

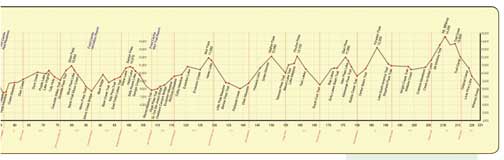

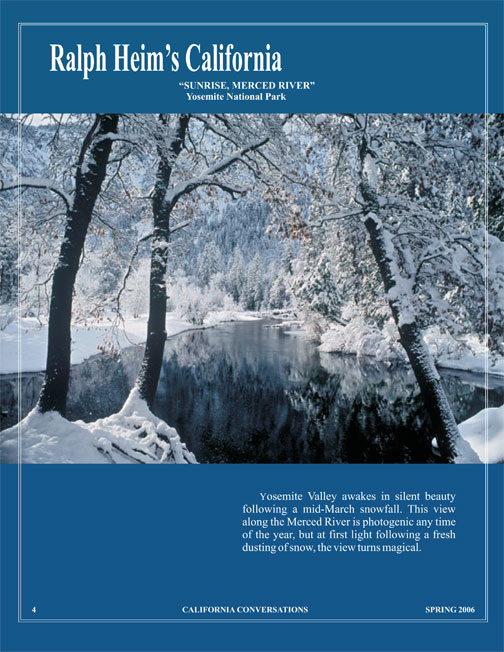

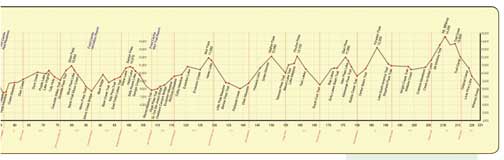

The John Muir Trail is in the Sierra Nevadas. It runs through three national parks and takes hikers who can withstand the elements through the Yosemite Valley to the summit of Mount Whitney.

Once Deanna and Steve made the decision to hike the John Muir Trail, they got serious about the planning. “The physical training was not a big issue for us,” Deanna said. “However, we started planning the food, mileage per day, anticipating the elevation gains and losses, and the places on the trail where we would rest during the day and sleep at night. I wasn’t fearful physically, I was just concerned about having the right gear and how it would be out there without much of a shower.”

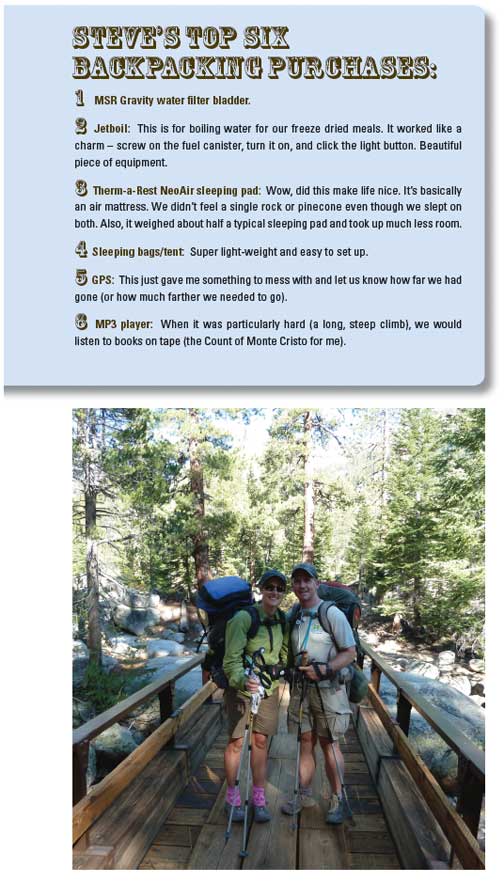

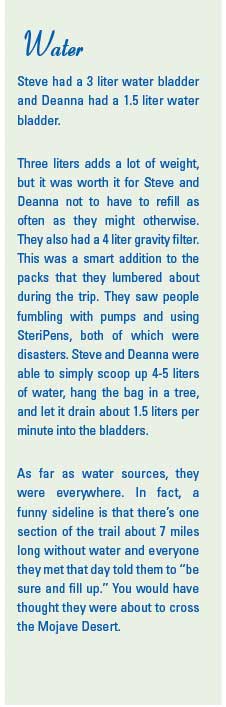

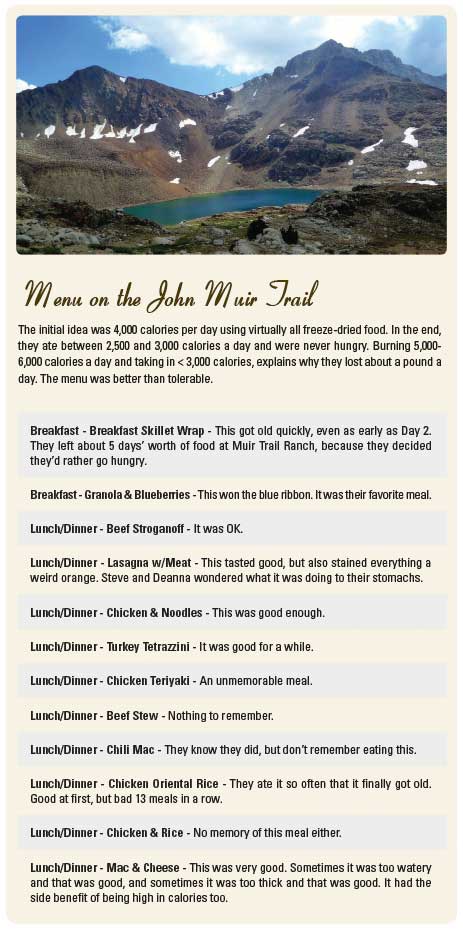

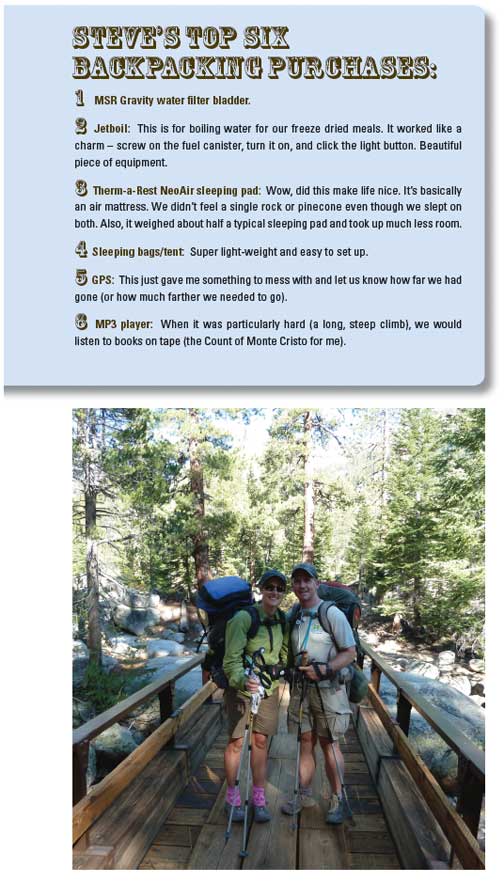

Steve charted their food on an Excel spreadsheet; calories per pound, per day, per person. Ultimately, Deanna’s backpack was 35 pounds starting and Steve’s was 45 pounds. Steve carried the extra gear like the tent and the gravity inline water filter system. They packed for the first six days and shipped the rest of the food to Trail Ranch, which is the halfway point.

“We got a 5-gallon bucket from Home Depot, packed it with supplies and mailed it to ourselves at Trail Ranch. We received a return receipt to guarantee its delivery. The folks at Trail Ranch kept it for us until we arrived. We just had to show our ID at the ranch and pick it up.”

“The limitation on the food was putting it in a bear-safe canister. You cannot hike through Yosemite without your food in a bear-safe canister. Those are the rules. It is for the bears’ protection and for yours.”

“When you’re really hungry and you’re losing a pound a day, it’s pretty good. We will take more trail mix next time, but we mostly had Mountain House dehydrated food and it was pretty good. You can exchange things with stuff other people have left at Trail Ranch. We actually mailed more than we could carry and so things we didn’t care for anymore were left at the Ranch and we took other things that looked more appetizing.”

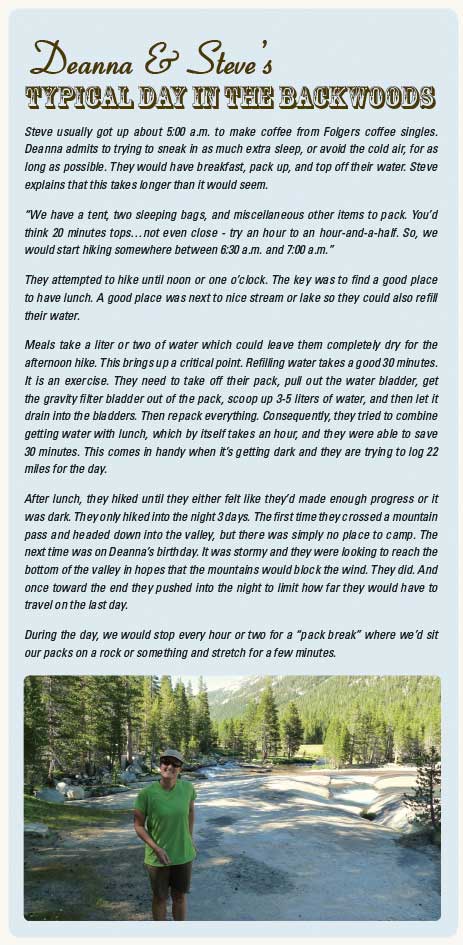

“Steve would get up at 5:00 a.m. and get his coffee and I would get up at 5:30 a.m. It was so cold in the morning. We would have a little breakfast and I would drink some tea and we would pack up and head out between 6:30 a.m. and 7:00 a.m. We would hike until about 1:00 p.m. We would eat lunch, which would take about 45 minutes to an hour. Some nights we weren’t at a spot where we wanted to camp so we would keep going. Some nights we set up camp at a decent time.”

We asked Deanna if there were ever days after lunch that she just didn’t want to get going again.

“I never let my mind go there because I knew we had to keep going. We had a timeframe. The only thing about the timeframe is that it is not enough time to truly stop and take in the scenes that you want to. We stayed on the main route instead of detouring. If we did it again we’d take a few more days to enjoy it. The streams are so beautiful and it was fun to sit and relax by the stream, but we didn’t have a whole lot of time for things like that.”

On the Trail

Deanna and Steve met a few couples doing the same thing they were doing. They were on a different time schedule than the others so they eventually didn’t see them anymore.

“There weren’t a lot of people on the trail. Our busiest night was a place right out of Tuolumne Meadows. There were probably 15 tents or so by the stream. Most other nights we had the camp to ourselves. The Parks system has established spots that are cleared out and smooth and they want you to use those to camp; they don’t want you camping anywhere new. They want to try and preserve the trail as much as possible.”

We asked about the amenities along the way.

“The second day ends in Tuolumne and hikers can stop at a store if there is anything they need before beginning the length of the trip. The third day is outside of Mammoth, and they have a nice campground and also a backpacker’s shower. It is a cement hot spring shower that the water just pours out of.”

“After day three there was not another shower,” Deanna laughed. “Nope, no more showers. I didn’t really want to use soap or anything because it can be a problem on your skin…with the snakes and everything so I didn’t want soap on me.”

There is only one bathroom after that third day.

“There is a high traffic area somewhere about a week into it,” Deanna said. “It is hilarious because a ranger built this makeshift throne on top of a hill. It has a little wood plank and then a toilet and you’re kind of just out in the open. Steve saw the sign that said to use the bathroom up the hill. He went up and then comes back and said it was great. So I go up there and the sun is coming up and I look around and it is out in the open and anybody walking up this trail would see me. I didn’t find it very enchanting myself.”

The Best Part of the Hike

Deanna said that the best part of the trip was the companionship. It wasn’t a valentine to her husband, but an immediate answer and an acknowledgement that she and Steve do well being in situations most us of would call extreme.

“We’ve done so much stuff together that inevitably when one of us gets tired the other one may have more energy. We feed off each other. We had so much fun and, for as long as it was, I really wasn’t ready for it to end. I wanted to get a shower but it was really a great trip.”

The second best part, easily, according to both Deanna and Steve, was the scenery.