Written by Aaron Read & Associates

Published Issue: Summer 2011

You can read the books about California history or you can make it fun and spend some time with Curren Price and listen to stories first-hand.

The erudite leader of the California Legislative Black Caucus has advantages. He’s a senator – not a bad way to be introduced and the kind of job that gets most people calling you back. He’s been both a witness and a participant to a generation of change. He is tall, loosely handsome, still curious at sixty, with a smile that is clever and turns teasing and lets you know he realized a long time ago that he is smart enough not to bother proving it. His eyes hold a rich color and don’t have any sign of burnout or cynicism. A lifetime of travel has taught him to be direct.

Curren’s disposition in private seems more fitting for a college professor than a politician. He appears younger in person than on television or in newspapers because the white in his beard becomes less noticeable the more animated he becomes. He commands through detail rather than volume, and it is not unusual for him to get caught up in laughter. One of his friends in the Legislature said if the Black Caucus was Motown, Curren would be Marvin Gaye.

Curren circles the rim of a glass with his fingers when he drinks. You get the sense he is no stranger to the pleasures of a long night. Curren has an unforced quality that is appreciated in people more often than it is seen, and it is a comfort with himself that allows others to relax in his company.

His stories have a freshness. They are told without urgency.

Inglewood 1960s

Inglewood’s early history can be traced to the beginning of the 20th century when it became the place where Los Angeles buried their dead and the Klu Klux Klan roamed after sunset with impunity. It grew into a working community catering to the aircraft industry and soldiers returning from World War II. Citation became the first million dollar horse at Inglewood’s Hollywood Park racetrack in 1951. At the time of the 1960 census there were 29 blacks living in Inglewood and none attended the local schools. It was ultimately made famous by the discarded Fabulous Forum and the fast break Los Angeles Lakers of Kareem and Magic. Inglewood is resilient. Through tough times it remains a vibrant place and was named an All-American City in 2009.

I am a product of the 1960s. I was in 8th grade during the Watts riots, and I remember seeing the Jeeps coming down the street. It wasn’t too long afterward that black student unions were being formed in our schools. They became the grassroots precursor to the Black Panther Party.

This whole thing with black consciousness, black awareness began filtering at every level. At colleges we had new graduate programs created in Black Studies that fundamentally changed the way curriculum was viewed. It was the beginning of ethnic studies. In the community, you had the Panthers organizing to bring about self-sufficiency and self-reliance. At that time, looking back, we can see that the Panthers were progressive in their promotion of lunch programs, health programs, and transportation programs that reach a totally unserved population.

I was influenced by it all. You had to be.

Curren entered Inglewood’s Morningside High School in the middle of the 1960s. He was popular, a vice-president and president a couple of years and then student body president of the predominantly Anglo-Caucasian school. It was 1968, a bloody year when the world was watching the explosive ugliness of the Tet Offensive, one of the turning points of the Vietnam War; the country was enduring the killings of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy; and Curren’s own city was being changed utterly by the fear-mongering associated with block busting and white flight.

Realtors would come through our area trying to get people to sell. They were scaring people that property values were going to bottom-out and if you didn’t leave you might get caught up in the rioting we’d seen in Watts. Block busting was telling the neighbors you better run while you can because the blacks are coming.

And it worked. The demographic did change dramatically.

Over the next ten years my neighborhood went from predominantly white to probably predominantly African-American in the ‘80s. By the mid-’90s there was another shift and it became predominantly Latino. The world literally began changing colors before our eyes.

We were one of the first black families in Inglewood. My dad was a merchant marine, a postal worker who also worked as an insurance agent, a salesman, he ran a small business and he made his mark in real estate. He believed in work. He was tall and charming, and dark-complected, and he got in trouble with alcohol. He beat it after a difficult struggle and was moved enough by the experience to become a drug and alcohol counselor.

My parents were divorced when my brother and I were rather young, but my dad was always in my life. There was a lot of personality there, and throughout his life he always remained a very positive figure in my life.

My mother will soon celebrate her 84th birthday. She retired as an LA County Clerk in the tax assessor’s office more than thirty years ago. She’s been retired almost as long as she worked.

You know, she was just a working class mom, a single mother, who worked hard, and always had us in activities. She believed it was important to keep me busy and from a very young age I had an after-school job. I was in the church choir. I was in Little League baseball. She was not going to let me run wild.

Black Awareness

Morningside High School was opened in 1951. Curren is listed as one of the distinguished graduates, and they make mention that before he was elected to the State Assembly and the State Senate, Curren failed in his effort to become the Mayor of Inglewood.

In my high school environment of fifty black students out of a thousand, we had a little area where all the blacks congregated. Certainly, we may have put some restrictions on ourselves, you know. I hung out with them. I also hung out with everybody else. So, I didn’t allow myself to feel consigned to a certain area or to a certain fate.

My parents emphasized education. It was a foregone conclusion that my brother and I would go to college.

My high school counselor said, “You know, Curren, your grades are just so-so. Maybe you should go to a community college for a couple of years.” I said, “Harvard, Yale…I’m shooting for the stars, right.” (Laughs) I got accepted at San Francisco State and Howard University, a black university in DC.

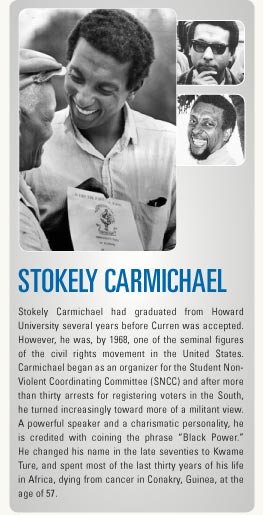

My dad, not really embracing this black power, black revolution stuff, said, “You’re not going to Howard. That’s where Stokely Carmichael and the other black radicals go to school.”

This is 1968. Stokely got everyone’s attention by being militant before anyone else. Martin Luther King was talking peaceful resistance while Stokely was demanding black separatism and confronting racism with the same force racists perpetuated their hatred. I think now that my dad and people of his generation had not heard the kind of talk from black men that was coming from Stokely. It was not easy for them.

San Francisco State

San Francisco State

I went to San Francisco State and, of course, I got involved with the student movement on campus. There were demonstrations for one reason or another everyday. It was a very charged environment. Everything was changing so fast in America and the college campus was in the center of it. There were sit-ins against the war and kids were trying to hold the faculty and the administration more accountable on social issues. And, sometimes things turned violent.

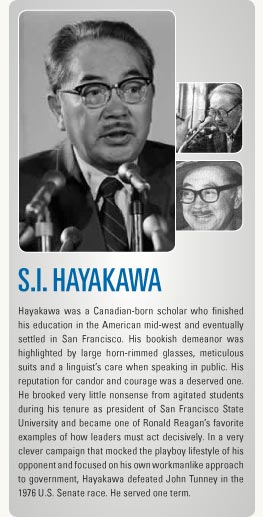

The President of San Francisco State was S. I. Hayakawa. He was an old guy who was known for being a linguist and an intellectual of some note. Not unlike most of the faculty, his world view was a view of a different time. There was no compromise in his manner and he confronted the students during the riots. He personally pulled the plug on their microphones to silence them. I saw him wearing his trademark tam-o’-shanter and climbing on tables and yelling at folks. It worked for him. He shut down the campus completely in the second semester of my freshman year. (Laughs) I’m at a college where there are no classes.

I learned a great deal about California politics by watching Hayakawa. The electorate in our state will consider voting for completely different types of candidates if they believe the person can do the job. Before the rioting, no one would have looked at Hayakawa as a national figure. After he shut down the college, the voters saw him as a person of action and elected him to the U.S. Senate.

My dad was concerned that I wasn’t focusing on the education. In his view, I was not in school to demonstrate or change the world. I was there to stick to my books and graduate. There was a bit of a generation gap. And it wasn’t made easier when I had the big natural, sunglasses, the goatee; you know all the accoutrements of revolution and being anti-establishment.

It was the beginning of colleges becoming more experimental and less dogmatic. The pressure applied by students resulted in classes that just a few years earlier would have been inconceivable.

I eventually got accepted into a program called “The Freshman Program of Integrated Studies.” I was in a group with about 40 other kids and the classes were pass/fail. We were in this kind of cocoon, so when I left at the end of that semester, all I had were passes. I had no A, B, C grades and the other colleges were not sure how to handle transferring the units. I also still had to figure out how to finish my freshman year.

I ended up going to Dominguez Hills during the day and El Camino at night. I heard Stanford was recruiting, all the usual stuff, looking for minorities, looking for diversity, blah, blah, blah, in 1969. I got in as a sophomore.

Of course, I got active again in the Black Student Union and community stuff. I did a home improvement project in East Palo Alto. It was a black enclave we called Nairobi, back in the day.

I also learned about a Stanford overseas program. I had not been many places and now I’m hearing about the possibility of getting college credits for studying in Europe. I apply. I get accepted. I go to Italy with the promise that I’m going to learn Italian. I’m almost 21 years old.

I spent six months in Italy and traveling through Europe. Then I proposed to the administration that I be given a travel grant to go to Africa and compare the attitudes of African students with African-American students on issues of integration, separation, liberation, all the buzz words at the time. Two days before we were supposed to return to the States the proposal for $7,000 was approved.

The overseas programs in the American colleges were popularized by the successes of the Peace Corps. It was an intensely optimistic idea that an exchange system of our best and brightest young people would result in the next generation of world leaders finding common goals. Also, similar to the early years of the Peace Corps, the students were given a great deal of freedom as they charted their course.

I went to a travel agency and they had this map of Africa on the desk. I got a ticket that took me from Rome to Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia, Zaire, Congo, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Nigeria, and Cameroon.

It was a poignant moment when I actually touched down in Africa. I was back home. It was amazing looking around, seeing all the people who looked like me. There was a lot of interest, a lot of curiosity, you know, a lot of camaraderie.

I hitchhiked from the East Coast to the West Coast by myself with nothing but a backpack and a suitcase. I would go to a university, meet some people on campus, and stay in a dorm for a couple of days. The longest I stayed was about a week when some girls took me in. I felt safe everywhere I went. I traveled freely.

American students at that time had greater access to information. I’d say the learning was just as intense in Africa. The social part was the same. I mean, the kids knew the western songs, the styles, so it’s not really culture shock. They were smoking weed and drinking beer like kids were doing every place else in the world.

In Africa at the beginning of the ‘70s there were remnants of colonialism. You’d go into shops and you’d see dark-skinned Africans doing menial work and the light skinned blacks, Asians or whites in control. It was very evident in housing. The governments were not totally free. The topic of discussion was how things were going to change. They were going to take a page from our black brothers in the United States - black power, you know.

I had an opportunity to retrace those steps years later when I went as a businessman for a trading company. I was changed by what I saw and where I went. In law school I majored in international law.

There were not many American students before Curren who spent time traveling in Africa. He did not have a lot of reference points. He talks of having an initial vision of Africa as the Wild Kingdom. He did not get out into the bush, however, and the college campuses were in cities not unlike the United States and Europe.

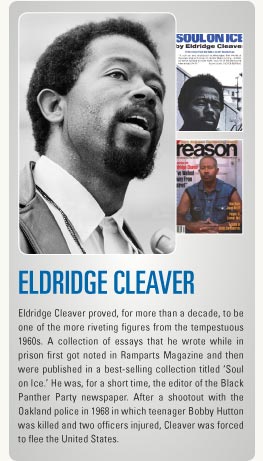

Curren took off for Algeria with two other men and a woman. In Algeria, he learned that perhaps the most famous of the American Black Panthers, Eldridge Cleaver, was living there in exile.

Algiers is at the very top of Algeria. You knew immediately it was a developing country, dusty roads and lots of people. There is a heavy Islamic influence and French speaking so there was a language barrier and culturally it was quite different. I remember a great combination of faces and colors. At the time we were there the weather was very pleasant. It was easy to get around in the city - hop in a taxi and you get to the place you wanted to be.

It was an adventure being in North Africa after traveling in Europe.

Eldridge Cleaver was in exile after a shootout between the Black Panthers and the Oakland police. A young Panther was killed and Cleaver was charged with murder. It certainly wasn’t a secret that he’d been given sanctuary in Algeria. We were able to find out where he was, and we went to the compound filled with that youthful confidence that they would just let us in. You know, we were African-American students checking in with Eldridge.

The compound was a walled-in space. They probably had guards out front. I don’t remember, and I know we moved around inside and outside without interference. There were several residences on the compound. There was a whole cadre of Cleaver’s associates who were there at that time.

Cleaver is largely lost to history now, but at this point he was a major American figure worldwide. He’d written the best seller ‘Soul on Ice’ during his time in prison. It was mandatory reading. He was the face of the new black culture, the Minister of Information for the Black Panther Party, the strong-arm storyteller of the real black experience, and he was the darling of all the revolutionaries.

Cleaver is largely lost to history now, but at this point he was a major American figure worldwide. He’d written the best seller ‘Soul on Ice’ during his time in prison. It was mandatory reading. He was the face of the new black culture, the Minister of Information for the Black Panther Party, the strong-arm storyteller of the real black experience, and he was the darling of all the revolutionaries.

We go to the compound, and it went like we thought it would. We knock on the door, and they let us in, you know, students from the US, black students are here. Oh, come on in, what’s going on, where have you guys been, what’s new, what are you doing? What’s going on at home, what are Americans thinking about black power – and Cleaver himself was accessible. It wasn’t like we had to wait to have an audience with him.

Cleaver was about six feet tall and in good shape. We were traveling with a young woman and he liked her very much. He was always dressed very casually. Very sharp. Inquisitive mind. He was calm. He didn’t raise his voice. Very controlled. He engaged us in conversations about separation issues, liberation, Pan-Africanism, and what was happening in the States. We ate together everyday…we were star struck with him asking us what was going on, asking us what our opinions are about the movement, the revolution.

I don’t think he was losing touch with America. He probably had a steady flow of folks coming to him. I think he was homesick. He couldn’t go home, and I think he knew that for the revolution he thought possible to take place, it was going to take a great deal more work.

He never left the compound. (Pause) I have certainly reflected on my time in Algeria and appreciated it even more as I got older. Cleaver encouraged us to stay in school and get our degrees in whatever we were doing. It was very empowering. (Laughs) He turned out to be more conservative at that time, more like my dad giving paternal advice.

He went through lots of changes in his later years (patient smile and lifting of his hands). I was very impressionable at the time. He was very…well, he was never a hero, but he was certainly important in my own little world. He got lost himself and when he eventually got back to the United States the issues had passed him by. By the time he died no one even noticed him anymore.

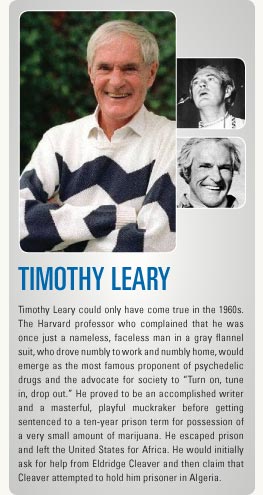

I saw Timothy Leary moving in and out of the rooms on the compound. He was in exile from America for drug charges, and he was always smiling. He was an old hippie to me then, although he wasn’t that old now that I’m older myself. I

remember him being on cloud 9, literally. Peace, love and soul. Peace, love and soul. There were never any in-depth discussions with him. I’m not sure what the drug laws were in the rest of Algeria, but it was not Islamic on the compound.

Leary and Cleaver were in the same place regularly, as I remember. I don’t really recall any interaction. There could have been. The impression I recall was Leary and Cleaver were cordial. I do know the relationship between the two of them did not end well.

I don’t remember Leary trying to get us stoned. I’ll say if he did he probably succeeded.

It was a remarkable time politically and socially. There were new voices. There were points of view that had been ignored and were now being heard. It was exciting. I do know for me personally the world seemed smaller after travelling. I had a point of reference.

Cleaver died young, but long after he ceased being an important figure. He never found his way or voice after returning to America and he dabbled in Mormonism, peculiar fashion designs, being Republican and battling addiction. Timothy Leary suffered a similar fate. His moment in the sun was brief and he ended up being a noisemaker without an audience. After he died, his ashes were shot into space.

Black power was a significant influence on everybody who was growing up during that period. A lot of self-awareness was going on, a lot of self-understanding. It transformed from a situation where blacks were not getting a higher education in real numbers, to a period where anyone could achieve anything they believed in. There were lots of firsts during that period. It was an empowering time, one that gave us a level of self-confidence, understanding, a better appreciation of history and how to make history, and a desire to go forward.

A feeling of black pride and black power resulted in us not just being relegated to second-class citizenship, but having a chance to step up to the plate. Blacks of my generation, because of our education, have made achievements far beyond anything our parents or white people of that generation could have imagined. The result of the sixties is a new African-American influence in the mainstream of political thought.

The challenges now, however, are terribly different, especially in the inner cities, where the drugs and guns and gangs are a presence. There is a crisis of education and health. Look, there’s no magic wand that was waved during the sixties and a new guarantee that everything was going to be peachy keen now. In fact, some of those situations now are worse. I’d say there’s not been a progress sustained. You know, you don’t have as many black kids, certainly black boys, in college now.

We’ve seen a transition where gang activity has wiped out a whole generation. I’m hoping that increasing awareness will make it clear that gangs are not the way to go. Mentoring programs, pipeline programs, educational programs, tutoring programs, are the way to go in 2011.

We have important work ahead of us. I don’t want my generation to be the one that had greater opportunities than the ones preceding us and, terrible if it happens, the one following us.

Politics

Curren’s first run for office was 1993. He was 43. He’d come back home, local boy makes good, Stanford, having lived in DC about ten years with an exciting job working for a communications company that was cutting edge. It was during the open spy policy for the FCC. Curren’s company was sought out to do engineering for companies who ordered large satellites. He got involved with marketing and forecasting. He was talking with the NFL because they wanted to do national games. He was in Sweden with Volvo. He got involved with cellular technology.

I became an effective advocate for small businesses wanting to succeed, and I’m proud that I was an asset to citizen involvement. Now, I’m happy to be in the Legislature at this time in my life, at this time in the life of the state. It’s a critical period to be involved, and I’ve got a voice to lift in the debate.

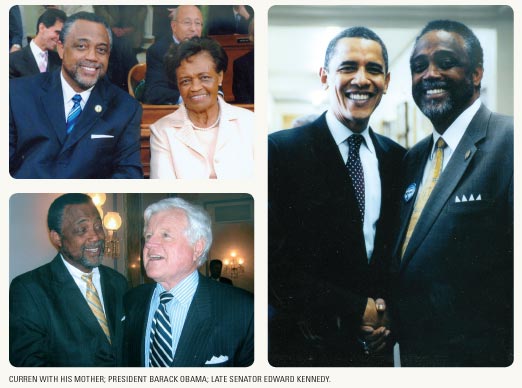

Curren was elected by his peers to chair the Black Caucus in the California Legislature. He is known for attracting talent and has a highly disciplined and respected personal staff. He was also recently named the chair of the key Business and Professions Committee and takes charge of their veteran team that is considered one of the best in the Capitol. He is in a position to help shape California.