Written by Terence McHale

Published Issue: Summer 2007

THE SPEAKER

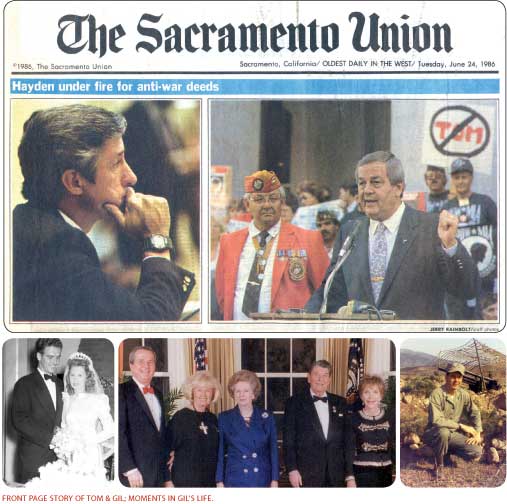

Twenty-one years later, Willie Brown, wearing his trademark fedora inside, laughing, interrupted by a little boy pushed forward by his mother to have his picture taken with him, stopped in the hallway of the Capitol he once ruled, and acknowledged June 23, 1986.

There were thousands of days over the former Speaker’s sixteen years as the leader of the Assembly, most of them filled with the compliments of power and the drudgery of milk nursing members, but Willie remembered clearly the day Gil Ferguson, the dapper, defiant, war hero from Orange County introduced the resolution to expel the brilliant iconoclast Tom Hayden from the Legislature.

The charge was found in a 1952 addendum to the California Constitution. Article 7, Section 9 says in essence (and we draw some distinction here since Legislative Counsel ruled it was not germane in the Hayden case a year before the resolution ever reached the floor of the Legislature) that anyone who advocates the support of a foreign government during hostilities is ineligible for state office.

“Did you tell Ferguson you hated the son-of-a-bitch as much as he did?” I ask. “Did you say you’d let Ferguson bring up the resolution to expel Hayden, but you wouldn’t let it pass?”

“It was an unforgettable day,” Willie said.

“So it’s true?”

“Maybe.”

GIL FERGUSON AND TOM HAYDEN

There is a description of Gil Ferguson. Gil was with a group of colleagues who described themselves with a self-congratulatory air as the “Cavemen” because of their conservative views.

Ferguson was much taller than the others. Gil’s grayish-brown hair was cut by someone who knew what they were doing and was styled instead of barbered. He was wearing a pale blue blazer, a pale shirt, a dark tie, and gold slacks. His shoes looked like they were handmade. The meticulousness was unforced. Nobody else could have pulled it off, maybe Willie, a stylishness that would have been foppish on anyone else, and never for a moment did anyone doubt Gil was the dominating presence in his conversation.

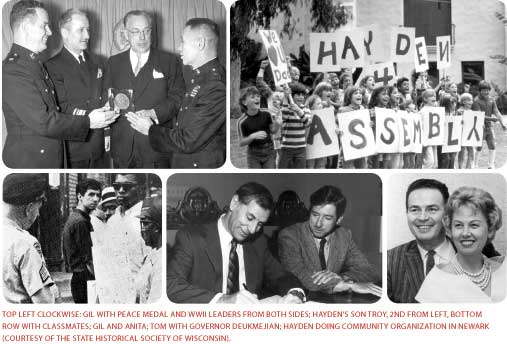

Gil was called the “Real McCoy.” He sailed his own boat in the same Orange County regatta that included John Wayne. The truth, of course, is that Gil did in life what the Duke got famous for doing on film. When his company commander was killed in battle, Gil Ferguson was given the job. That’s tough work. It was easier for the actor since he only needed to pretend courage under fire.

The Legislature was a frustrating experience at times because it was controlled by Democrats, dreaded liberals, no less. Gil recognized that at best, the minority party was in place to limit policy rather than make it. He did manage to write the first pieces of legislation championing term limits, and there are bills carrying his name that protect children from predators. Toward the end of his career, his libertarian roots surfaced and Gil supported medicinal marijuana. His view was heard most often on budget issues that required a two-thirds vote and forced backroom negotiations to be made.

Gil refused to acquiesce when the Democrats told him the argument as to whether or not Tom Hayden belonged in the Legislature was already resolved.

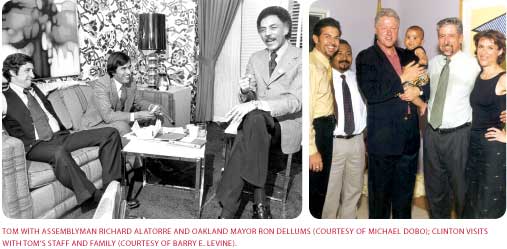

Tom Hayden was a marquee item by the time he was elected to the Assembly in 1982. He was the first of the student activists to get a name, the chief writer of the seminal Port Huron Statement, a Utopian document that seems mostly absurd fifty years later except that it captures completely the daring and the dream of those who believed the 1960s would be the decade in which a new generation of ideas would make the world an ideal place. It was called “A Manifesto of Hope.’’ Hayden admits that in their passion they made ‘sophomoric proclamations,’ yet four and a half decades before Barack Obama began writing the themes for his nomination they’d become the messengers of something new.

Hayden was at the early meetings of the Students for a Democratic Society, became an activist president of the organization and got caught up in the language and ideology of not being bourgeois. He spoke elegantly of the need to find a political vehicle for anti-poverty programs. He got his ass kicked by racist thugs in Mississippi. By 1975, the FBI had 22,000 pages of information in their Tom Hayden file. Hayden did not back down when his politics caused a painful rift of almost two decades between himself and his father.

Hayden was in the trenches during the early stages of the civil rights movement. He and his first wife, Casey, blonde and gutsy, lived in hidden away safe houses at night after spending their days registering black voters in a virulent South.

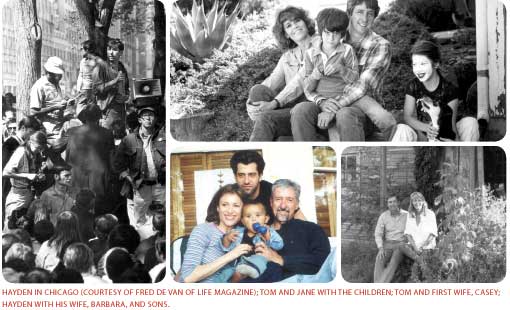

He was a chief figure in the anti-war movement, one of the Chicago Seven charged with conspiracy to riot at the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

His second wife was Jane Fonda. It was their trips to Vietnam during the height of the war that would cross him with Gil Ferguson.

In the 1970s, Tom ran against the faux Kennedy, the son of a heavyweight champion, incumbent John Tunney, and made a real contest of what was previously considered a safe United States Senate race. His ideas about rent control were revolutionary and pragmatic at the same time. The way he challenged insurance companies for crimes committed during slavery bothered some as revisionist and vengeful history. His critics would say he chased the spotlight; a lot of it true since his supporters insisted he was challenging an ugly status quo that did not do well when it was exposed by something bright.

The liberals in the California Assembly were thrilled by Tom Hayden’s election. They expected the firebrand activist, the revolutionary.

They got instead a man who, in private, is reflective, not someone naturally trusting of anyone. At his core, a Midwesterner, a man whose ideas were best conveyed in writings and not rousing speeches and, in the small confines of a Legislature, someone who retreated most often to his own counsel. Part of his appeal is Hayden doesn’t pander to his own image. He didn’t make any effort to be popular with his colleagues and, in fact, barely mentioned his legislative career in his autobiography, yet when he was termed out after eighteen years, a Los Angeles Times reporter not given to hyperbole called him the conscience of the Senate. The farewell ceremony on the Senate floor was filled with heartfelt tributes from Senators who admitted they looked to him as the best example of public service.

His former chief of staff, on an airplane trip in which he talked fondly of working for Hayden, says Tom would tolerate mistakes but not a lack of passion. He took his staff on bus trips through the district he represented so they could understand the people who expected him to speak for them.

Gil Ferguson and Tom Hayden were born seventeen years apart.

They are proof that generations are most often identified by events rather than delineated by years.

“World War II changed everything for me,” Ferguson told California Conversations. “Kids that grew up together in families that never moved more than one hundred miles away were now all over the world. The bonds were broken. We saw things and did things that took us away from our neighborhoods. We built new lives. There was no way I could go back and pretend Missouri was the whole world.”

“The truth is, if I had been five years older I wouldn’t have lived the life I’ve led,” Hayden said. “My coming of age, so to speak, intersected exactly with John Kennedy’s election, the beginning of sit-ins by black students in the South, the introduction of the pill. I can’t even remember everything that happened when I graduated college in 1961, but it was enough to alter the social situation for someone like me. What I brought to it was a kind of non-conforming and anti-authority spirit.”

MEETING TOM HAYDEN

We called Tom Hayden and interrupted him cooking dinner for his young son, a grade-schooler who belongs to Tom and his third wife, and asked if he would talk about Gil Ferguson. He was not interested in rehashing old history. Reluctantly, he asked if we could conduct the interview through email. We refused, promising not to open his refrigerator, pet his dog or use his bathroom, but we wanted the interview in person.

Hayden eventually agreed to meet at one o’clock in the afternoon at his Southern California office.

We had not seen Hayden since he left the Legislature seven years earlier, after eighteen years in the Assembly and Senate. He is no longer a young man. His thick hair is completely white and his goatee is a bit scraggly with errant whiskers on his otherwise smooth cheeks. He was never handsome. He is appealing, a face that should be dominated by his large nose, yet isn’t, getting old everywhere but his eyes, curious, and the look is so minus any bullshit that you almost feel like you have to explain your presence.

He is not as tall as we remember, maybe five foot nine, and he is still slim, the beginning of a paunch that doesn’t take away from him being athletic enough to still play, the oldest player on his team, in an adult hard ball baseball league. He is in his late sixties. It doesn’t seem possible, for many reasons, partly the thought of the student activist examining life though the prism of senior citizenship, and partly because so much of what we associate with Hayden involves a rebellion we believe belongs to the young.

His handshake is firm. Hayden teaches college. The stories he can tell about the places he’s been and people he knew must make history seem very real to his students. He met Martin Luther King ‘in the days before we thought about taking pictures of such things.’ He was close enough to Bobby Kennedy to be someone who matters to his kids. He inquires if we are hungry. He seems disappointed for a moment that we aren’t, says he is, and leads us through the reception area of an office to a tiny kitchen where he makes a peanut butter and jelly sandwich.

His own office is small, one room and a bathroom. The front and back doors are opposite each other and there is a nice breeze. The office has big rugs covering the carpet, a comfortable couch, a small desk with a computer, and books in bookshelves, books on the floor, books on chairs, books covering the pictures of him with famous figures, books that have the dense titles of academia and are bent in the corner or spread even at the spine, books, books, books. You get the sense that with enough peanut butter and jelly Hayden could hole up in this spot for a long time.

MICHIGAN

Hayden’s father was an accountant. His mother was a librarian.

“Their jobs were important to them,” Hayden remembers. “My parents were of lower middle class origin, and they moved up the ladder from immigrant status, and working class, to white collar and being part of the amorphous middle class.”

The Second World War, like all previous wars, was fought by men from small towns. Jack Hayden left Royal Oak, Michigan, and his wife Genevieve, called Gene, when Tom was four, barely old enough to sing the Marine Corp Hymn. Uncle Cy, the only brother among a dozen sisters on his mother’s side went too. Jack Hayden would return changed, distant, more semper fi with his soldier buddies around the bar at the Veteran’s Lodge than part of the family, and a divorce would result. Uncle Cy was killed when his machine gun malfunctioned.

Tom Hayden: In my mind I’m sure the linkages were made, you know, something happened to my dad and he came back different, and not for the better. But, being a marine of that generation, which would be Gil Ferguson’s generation, he tended toward believing that this was the best country in the world, and the government always told the truth. Those assumptions, I think, allowed him to live his private life. My parents didn’t think of themselves as being in a social structure or an economy or a political structure. They didn’t have a way of knowing what was disturbing them. My dad wanted to watch Sam Snead and Ben Hogan play golf. He wanted to fish. The early sign that something had gone wrong was when he noticed people in Michigan buying Japanese cars.

MEETING GIL FERGUSON

A long time Republican staffer who retired years ago said there are three undisputable truths about Gil Ferguson.

He was the kind of soldier offered battlefield promotions, and in three wars, often under the worst conditions, he proved himself to be the best man.

In a picture in the Oval Office with the Prime Minister of England and Ronald Reagan, he does not seem out of place. His friends said that Gil was not easily impressed, and felt comfortable anywhere he wanted to be. Gil was accustomed to making decisions and it was common in the Republican Caucus for the members to wait to hear Gil’s ideas before weighing in.

The third was that Gil loved his wife, Anita, absolutely, that she was his partner in everything he did. She was described in the most complimentary, old-fashioned term as ‘lovely.’

We chased down a couple of numbers for Gil. The call came back from Anita. She was pleasant. She said Gil was in the hospital. He turned 84. We said we wanted to talk about the events of June 1986. She remembered it was the ‘Hayden problem.’ The timing didn’t seem great.

Anita called back to say Gil wanted to talk on Wednesday, in the morning, before he got tired, and he would answer any questions we wanted to ask.

We got to Orange County’s Hoag Hospital in time to negotiate the Pentagonal hallways to be at Gil’s room on time. He was an old man hooked up to tubes and sitting upright in a stiff chair by the bed. His hair was still carefully styled. He was freshly shaven. He was gaunt, yet wearing a hospital gown and with his socks pulled up just below the knees, his bearing was unbowed. This was his room. This was still his world.

MISSOURI

Baseball’s Gas House Gang of the 1930s is remembered even today by old timers as the meanest, wildest group of great players ever to dominate a stage in any American sport. The cop who worked the beat of the old St. Louis major league stadium was once a prospect himself. He grew up tough in the Ozarks. There was some schooling, not a lot, and he was a man who educated himself about the ways of the world. He threw his arm out in a freak deal firing a tennis ball around and lost his chance to play ball for a living. His name was Ferguson. He had four sons. All of his sons inherited his height and athleticism. Everyone in the family was expected to pull their own weight. The cop used his influence to get his third son, the thirteen-year-old, Gil, a solid junior high school pitcher, work as a clubhouse boy for the Cardinals. Gil kept the job from 1936 to 1940.

They didn’t have bottled beer then and one of Gil’s jobs was to go to the wooden keg and fill a tin bucket and bring it back to the dugout.

“The players were spitting at me and each other,” Gil said. “There were nights when half the players were in the bag and stumbled to their position. If the game went extra innings they were in trouble.”

Hall of Famer Dizzy Dean was their great pitcher and ringleader. Gil remembers him as ruinously wonderful and someone who shouldn’t be around children. He was all country-boy. All of them were. Legend has it that Dean’s career ended when his toe was broken during an All Star Game and he couldn’t adjust his pitching form.

Gil says Dean also hurt his index finger flicking the sulfur tops of his wooden matches to light cigarettes. They all smoked. They played hard, too. Pepper Martin, who Gil called “the Indian,” was the meanest of the bunch. There were bruises all over his body because he got in front of everything hit in his direction and refused to let a ball get by him.

“I learned from those guys that if you hit the ball, you got on base. Holy shit, these were men who no one gave anything to. They didn’t expect anything to be given to them. They made things happen.”

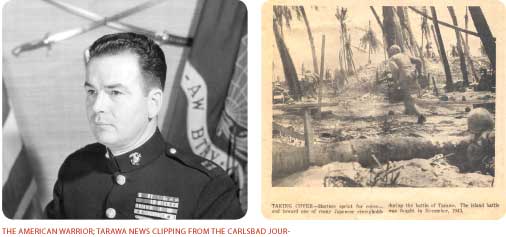

TARAWA

The four Ferguson boys would serve in World War II. They would all earn a Purple Heart. Gil joined the Marines because his family home was on the west side of the Mississippi, and he knew that meant being sent to California.

He proved adept with a rifle, and the Marines made him one of their youngest instructors. There are pictures to show what he looked like and for those who recall the Splendid Splinter, baseball’s Ted Williams, there is a physical similarity. If you don’t remember Ted Williams, splendid works on its own. Gil was a tall, slim, curly-haired kid.

California was a goddamn paradise. He loved the weather in San Diego. He said that if given his choice he would never move away from the ocean again. There were perfect breezes at night. It was a great life while much of the world was fighting. The war truth came home to him when one of his brothers was killed testing the B-17 bomber.

Gil asked to be sent into action. The Marines quickly accommodated his wishes, and only months later he was in a small landing craft approaching the island of Tarawa, the island the enemy boasted could not be taken. A member of the VFW didn’t mince words with us. “Tarawa was f***ing war.”

Gil Ferguson: We were singing Ta-ra-ra Boom-de-ay until we started hearing these banging sounds on the side of the boat and realized they were shooting at us. The boats were supposed to go all the way to the shore, but we hit a coral reef and were forced to stop 700 yards out. The sergeant stood up and said everybody out and the whole side of his face came down on us. He lived. I saw him years later and his face was stitched together, but he lived. I got out, and I had to climb over a barbed wire barrier. There were two Japanese in the water ahead of me. They seemed like giants. I shot them without even realizing what I was doing. I was in such a state that I emptied my gun without realizing it.

California Conversations: You killed two people just minutes into the battle?

Gil Ferguson: They were there, and I fired without thinking. There was no doubt we were there to fight.

CC: The battle lasted three days?

GF: 76 straight hours. I spent a lot of it running to these little areas called pillboxes where the enemy was hiding and pointing them out to my lieutenant and captain.

CC: You’re being shot at while you do this...are you scared?

GF: Holy shit, I’m terrified. And after a while I’m tired, exhausted, and you just start thinking if it’s my time I’m going to get hit. You try not to be careless. You can’t help but become fatalistic.

CC: Were you wounded?

GF: I was shot in the leg. There was also little stuff from hand-to-hand combat, bayonets, and a grenade blew up near me and I was unconscious for a while.

CC: For how long?

GF: I don’t know. It could have been ten seconds or five minutes, I don’t know.

CC: Can you describe being in battle?

GF: I’ve been in hundreds of battles and none of them were like Tarawa. The entire battle took place in a space of about 600 yards. We were always on the alert. In other battles you think about the terrible living conditions, where people are sick all the time and you’re dealing with what it takes to handle the needs of the troops in the field. At Tarawa it was about staying alive. I remember there was a sharpshooter who had some of our men pinned down and nobody could get him. I asked a guy to watch close, and I shot at him and asked my guy if he could tell where the bullet hit. He told me. I adjusted my next shot and killed the enemy.

CC: Had you ever seen a dead person before?

GF: I saw a guy who got killed in a car accident when I was a kid. I saw a lot of death at Tarawa, and I got used to it fast. The first time someone shoots at you, it changes your thinking forever. You realize how temporary everything is.

Tarawa was the most violent battle in Marine Corps history. Three thousand Americans died. The Japanese swore that they would fight to the last man. They damn near did. The courage on both sides was enough for one veteran to comment that the uncommon became common. Out of the 4,700 enemy defenders, only five Japanese survived. Asked later if he was plagued by nightmares from all the killing, Gil said you can see with your heart and emotions or you can keep it as impersonal as possible. Even when his best friend was killed, “I never took it to a place where you dwell on things.”

Ferguson was Marine Corps material. In the three years from his high school graduation to the end of the war, Ferguson rose to the rank of Lieutenant and was being offered inducements to stay in the service. Out of a recommended pool of 23,000, the Marines offered 18 young men full-paid scholarships to the college of their choice.

Gil Ferguson: I chose USC because I thought it was UCLA. I told the cab driver when he drove into the parking lot that he was making a terrible mistake (laughs). The school I chose has beautiful green lawns all around it.

CC: You were one of the youngest Marines, but one of the older college freshmen?

GF: That’s true.

CC: Must have been culture shock after the war?

GF: It was a different time, but I was actually chosen Freshman Class King at USC.

CC: Do you campaign for something like that?

GF: (laughs) No. No one knew who I was. I had a fraternity brother who wanted to make sure someone from our fraternity got chosen, and he put it together for me to be elected. His name was Phil Burton.

CC: The late Congressman from San Francisco?

GF: (laughing) He was my roommate. This smart liberal with screwy ideas got his conservative friend elected.

CC: Were you close friends?

GF: I liked him. Phil was grading graduate papers as a freshman, but he also had some screwy ideas. He used to say we don’t have blacks in the fraternity. We said, no, they have their own fraternity. Then he said we don’t have any Jews in the fraternity, and we reminded him we’re a Christian fraternity. I loved him. Unfortunately, when he got older he became too remote and there was a glass of whiskey on his desk earlier and earlier in the day. Even his fellow Democrats didn’t trust him anymore. We didn’t look at things the same way. I think his heart was always in the right place.

CC: Wasn’t Jesse Unruh at USC at about the same time?

GF: He was there, too. He and Phil wanted to run everything. They didn’t want the Chancellor to run the University. Unruh was just a fat little guy with a heart of gold. Nobody ever thought he would amount to anything special.

CC: You met Anita at USC?

GF: I did. My fraternity brothers stood singing behind me, and her sorority sisters stood behind her when I gave her my fraternity pin. We were married within a year.

THE ACTIVIST

Tom Hayden sat with us on the comfortable couch in his small office. He’s smart, an odd observation, I guess among older men sitting together, but his answers are thoughtful without the need to struggle for the right word. He’s not pretentious. He says things that would sound like bullshit coming from anyone else, a blend of the passion and idealism and articulateness of the 1960s with the credence of someone who has spent almost half a century putting his views in front of the public.

California Conversations: What does injustice feel like physically for you? What happens? Does your stomach get upset? Does your head hurt?

Tom Hayden: A very good question. The word is ‘feel.’ I have a visceral reaction to it. Again, it is something that can be talked around, but can’t be put into words very clearly. The question for me now is where do the feelings come from that are violated? Some of the feelings come from our cultural heritage, in my case, an awareness that the Irish went through famine and oppression and discrimination. It also comes from what you learn in Middle America about the Bill of Rights, democracy, and the kind of things politicians repeat even if they don’t want you to act on them. But you sort of internalize the right to vote, the right to assemble, the right to protest, petition, and if any of these things are violated it can set off feelings.

CC: In 1961 you show up with the girl you haven’t married yet and tell your parents you’re leaving to register black voters in the South.

TH: Now I can understand what my parents were going through - that everything they’d devoted themselves to appeared to be lost. Their son was graduating from college. He was supposed to take a great job, upper class, maybe, and instead I was, in their view, throwing it all away.

CC: You went South in a Corvair?

TH: Station wagon. Dangerous car. In fact, I was driving south and it did just what Ralph Nader warned about. That’s the closest I ever came to losing my life. All of a sudden the car spun around and I was backwards and off the road.

CC: There were times in the South when you feared for your life?

TH: There were sharecroppers who were booted off their land and were living in tents in a small town near Memphis. We went with a carload of people and some food. They knew we were coming. We unloaded the food, and out of the darkness came the sheriff deputies. I remember my knees buckling. It wasn’t that I was afraid, but I learned that we’re subject to forces. I was looking them in the eye. I was talking to them. I was interviewing them, and I couldn’t stop my legs from shaking. There were times when we were at a disadvantage. We didn’t have guns, chains, baseball bats, and we didn’t want them. We didn’t believe in them. All I remember is more adrenaline than fear.

CC: A more prosaic question - how did you support yourself?

TH: You didn’t really need to. This is why it’s not a model for kids today. You could live on next to nothing. If you didn’t worry about the future, about savings, that would be another matter. There wasn’t much to worry about. You could ask your parents; you could ask your parent’s friends. I’m talking about asking for $25, here, all right. I remember we wanted to set the all-time lowest expenditure for food, like one dollar a day max per person. There was a way to do it on beans and rice. That was the Catholic voluntary poverty thing. In truth, it was cheaper and easier back then. It cost me $100 to go to the University of Michigan. I don’t remember if it was $100 a semester or $100 a year.

CC: In 1965, you go to Vietnam?

TH: I gave no thought as to the political consequences or image or anything like that...you know, in academia they always talk about the primary sources versus the secondary sources. My primary source is my personal experience. I always try to start there. My experience was that all of the civil rights and anti-poverty work that I was trying to carry out was doomed because of this war.

CC: To back up, were you too old for the draft?

TH: (laughs) They didn’t want me. I had my physical and they classified me 1Y, which is either troublemaker or asthma. It’s pretty arbitrary.

CC: What was the reason for the trip to Vietnam?

TH: I thought the big problem with Vietnam in 1965 was the utter blackout. Look, if I could get in, which the government said was impossible, why couldn’t reporters. Shortly after my first trip, Harrison Salisbury of the New York Times went and his stories broke the war open. The trip I took was what you would call today, Citizen’s Diplomacy. It included a range of activities, but it was all about breaking down the iron curtain of information.

CC: Who financed the trip?

TH: I don’t know.

CC: No?

TH: I think I raised the money from friends in the New York/New Jersey area. We’re talking about maybe $3,000.

CC: Was the trip legal?

TH: It was an act of civil disobedience. We went on the grounds that we have the right to travel anywhere. That is the heart of the American idea. We did not use our passports. We contacted the North Vietnamese government ahead, and they contacted the Communist governments in China, Russia, Czechoslovakia to let us land and stay in transit and take the next flight without using an American passport.

CC: The idea of the trip was to find out what wasn’t being told?

TH: I’m sure there was a mixture of aspirations to the trip, but getting an independent reading on who the Vietnamese were, what they were fighting for, what they wanted, and what the peace might look like was the opening of the door.

CC: How many trips to Vietnam did you actually make?

TH: Over a twelve-year period, probably four. Many Americans went. I went with Jane. We made a film. It was a strange trip, because we worked really hard on this film about who was on the other side and what was the solution to this, and we had, as they would say in Hollywood, access to some extraordinary locations, inside the demilitarized zones, which I don’t believe any Americans had ever seen, except commando units perhaps. Then the war ended. The film is kind of on the shelf.

CC: There’s the famous picture of Jane sitting on the gun. Did you realize that picture would haunt you for the rest of your lives?

TH: When was that...1972...1974? I don’t know how I could have prevented it...live by the media, die by the media. Jane made an unplanned stop along the road she was walking. What was she supposed to do, say no, I don’t want to take these five steps into this position...the spontaneity of it all?

CC: Well, yeah, she was certainly media wise. I mean it’s a provocative picture at best.

TH: Well, it certainly seemed to provoke some people. On the other hand, in polls she was one of the most popular women in the world. To me, it was her option, and if she had been media conscious she would not have done it. But being a free spirit, she’s perfectly entitled to it. People who hate her for it will have to live with it.

CC: Have the two of you talked about the picture and how it became enemy propaganda?

TH: She’s become more apologetic about it over the years.

CC: Do you understand why Gil Ferguson or veterans your father’s age would believe you provided succor to the enemy?

TH: I’m sorry they feel that way.

CC: I’m asking do you understand how…

TH: I understand where they’re coming from, but we’re not engaged in therapy here. It is a ridiculous notion to believe that the Vietnamese fought on because I made a trip there or Jane had her picture there. They lost two million people, and we lost the war because they outlasted us militarily. I’ve heard the Ferguson argument that we fought in wars to protect your right to dissent. No problem in that. But, not to give aid and comfort to the enemy, that’s where you get lost in words. Were the Vietnamese really our enemy? Were they an enemy in a legal sense? Was the war ever authorized? So, let’s get past that. What you get down to is whether or not you agree with my behavior. The question is whether or not I had a right to be in the Assembly having been voted on by a majority of the people.

LIFE ON THE SHORE OF PARADISE

Gil laughed and said he was reluctant to tell his buddies that after he left college he and Anita took over the interior decorating business that belonged to her father.

He was also called back to the Korean War. He was at the major battles of that skirmish, including one in which his “‘entire platoon was almost wiped out” and his “beloved Lieutenant was shot mercilessly in both legs and never walked again.” A veteran said it admiringly, when he explained, “there was no bullshit when it came to what Gil Ferguson did in Korea.”

Between the wars, Ferguson was much more the USC graduate than the kid from Missouri with the folks from the Ozarks. He went to work for one of the major companies in Orange County, becoming in a short time one of their major executives.

He and Anita got involved in real estate. They dabbled in moneymaking enterprises. More than one of their friends said the closeness between Gil and Anita could also be traced to her being able to step in and help run their businesses when Gil was called back to active duty. He did not rely on other people. She was the exception. He felt comfortable that she was there when the military called on him.

He was called early to Vietnam.

California Conversations: You were in Vietnam in 1965?

Gil Ferguson: I went as an advisor even before that. My tour in 1965 was my second one. We were fighting by then.

CC: Were you aware of Tom Hayden in 1965?

GF: Yeah. I’m aware there is someone named Tom Hayden, and he is part of a trip of Americans that has been paid for by North Vietnamese and the Chinese government who, by the way, are having a great revolution of their own and slaughtering millions. The trip is meant to persuade the world that they are a small country being bullied into submission by the giant United States of America.

CC: You’re convinced that the North Vietnamese and the Chinese paid for Hayden’s trips?

GF: I am convinced that’s what the FBI and CIA said. I’m also convinced that he left Vietnam and participated in a Young Communists meeting in Czechoslovakia in which he spoke in favor of the North Vietnamese. That is providing succor to the enemy.

CC: Were the Hayden trips important to the military in the 1960s?

GF: Hayden is not the number one thing on our screen, but when the officers got together and talked about how screwed up things were we talked about Tom Hayden and Jane Fonda.

CC: Hayden draws the distinction that the Vietnam War was a different kind of war than WWII and Korea.

GF: They were all different.

CC: Did we belong in Vietnam?

GF: Well, it depends on what you think the policies of America should be. More importantly, we actually believe that God made us to be free, and we put that in the Constitution, that we have rights - life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness - just a billion rights that we have by being here in this country. We created a government based on it. Now, you can’t ask Joe Smith down the block to send his son off to die in a war if the guys on both sides of the street aren’t going to do anything.

CC: Did the government lie to us about Vietnam?

GF: (Throws his hands up) The government lies to us everyday. Whether the government lied or not, there’s still no excuse for what Hayden did.

CC: Hayden and others say history has proven them right, that Vietnam was a bad idea and a bad war.

GF: Anybody who wants to oppose the war is probably within their right to oppose the war, and there may be good reason why they’re opposed to the war, and there is room to discuss those reasons, but there is no excuse for assisting the enemy against the United States.

CC: Senator Hayden says he was only there to get to the truth of what was happening.

GF: They were the guests of the enemy. They provided anti-American propaganda that was devastating. They made villains out of Americans in the middle of a war. Tom Hayden was a coward.

CC: You can say what you want about Hayden, and you obviously do, but Tom Hayden was not a coward.

GF: You don’t think so?

CC: No. This is a guy who left the safety of his college town to do what he thought was right in the segregated South and he faced incredible physical danger. He’s never been afraid to stand behind his beliefs.

GF: (pause) Yeah, I can believe that. I can believe he was courageous when it came to issues he thought were important. But, he was wrong on the war.

CC: What would you have wanted to see happen to Hayden and Fonda?

GF: I think there should have been a public trial. They should have gone to prison. It would have cured the problems we had with them later.

CC: You served in the Legislature with Tom Hayden for several years. Did the two of you ever speak?

GF: No. There were a couple of times that we found ourselves alone in a hallway. We nodded at each other. I always thought he was bit wooden. I never thought he had much personality.

JUNE 23, 1986

There was a bank robbery in Los Angeles and hostages were being held. It was the big story of the day. Television was covering it live, blanket coverage, something unusual for the time, and not much else was going to get any attention.

The rumblings of what would lead to the first Gulf War were the focus of national policy.

The summer was not too hot. The delta breezes were still present, and for those who hadn’t been in California before, the weather was yet another reminder of why the population of the state was growing by almost half a million a year.

Beautiful new homes were selling in our mid-sized cities for $100,000.

The Veterans of Foreign Wars, the VFW, were holding their annual convention at the Doubletree Hotel in Sacramento. In the middle of the afternoon more than three hundred former soldiers climbed onto buses for a rally on the west steps entrance to the California State Capitol.

A fiery congressman gave the morning speech at the hotel condemning Tom Hayden. All of the vitriol that could be mustered was used to foment the troops. At the steps, there was no doubt the vets would be greeted by one of their own, an old soldier they admired because even among themselves they admitted that none of them could match his war record, the Assemblyman from Orange County, Gil Ferguson.

Ferguson was 63 at the time. He stepped to the podium to the loud, echoing approval of the group. There was not much resemblance to the young soldier of Tarawa. He looked like someone who spent a great deal of time at an exclusive country club. Always natty, he was now much heavier, jowly, big, and his voice carried above the crowd.

The internal television network at the Capitol was not yet in place. There are thousands of hours of legislative drivel that are now memorialized. This day, unfortunately, is mostly lost.

Tom Hayden was popular in his district. He was a responsive legislator with a strong constituency support program. They overwhelmingly opposed the Ferguson resolution. There were also a handful of veterans willing to stand with him at a morning press conference, including one of three POWs released to Hayden years earlier by the North Vietnamese.

The Capitol Press Corp was much larger than it is now. Even the minor newspapers thought it was still important in the 1980s to have at least a token appearance at the State Capitol. The press conference was crowded; standing room only, when Hayden, black-haired, in the prime of his days, dressed in a sharp, dark suit, stepped to the stage in an unrepentant mood.

The Assembly Floor

The floor of the State Assembly is green. It dates back to the 1860s and still has the appearance of an old theater; the balcony is three rows deep and circles the desks of the legislators below. There is a large painting of Lincoln. It probably made sense when the state was new to memorialize the martyred president from Illinois. By 1986, California had heroes of her own, although it is doubtful an agreement could be reached on whose painting would serve as an appropriate substitute.

A valley legislator, still new to politics, viewed the scene from his own desk as an, “incredibly intense situation. It was the politics of old wounds. Old scabs were being ripped away. There was increased security. This was not an issue that could be negotiated. There was the feeling that surrounds an ugly fight.”

The issue for many legislators was a matter of loyalty, not only to a colleague, but to how they viewed themselves as Americans. The vote they were going to be asked to make involved the rarest of actions in a democracy - the removal of an elected official from their place in the Legislature.

Hayden was still larger than life to many of them. He sat at his desk with the calm of someone attending Mass. He did not look around when the Ferguson speech began. He also did not look down.

“Ferguson was a strong guy, but he was also very affable. His voice was different that day,” the former legislator remembers. “He was emotional. It wasn’t that he was going to break down. It was the personal nature of his attacks. All of the bitterness of Vietnam was present in his speech. No one moved. There was total silence and he had everyone’s complete attention.”

California Conversations: Did you know the outcome before you introduced the resolution on the floor?

Gil Ferguson: Willie told me he hated the son-of-a-bitch Hayden as much as I did. He said, “I’ll let you rant and rave and do your thing, but he’s a Democrat now. We’re going to have a vote, and you’re going to lose because the Democrats won’t vote against him.”

CC: Did you write your speech beforehand?

GF: I didn’t need to. These feelings were inside me for more than twenty years. I had notes just to make sure I didn’t go on too long. I spoke from my heart.

CC: Do you remember what you said?

GF: I provided a history of Hayden’s behavior and contrasted his actions against the behavior of people who opposed the war without crossing the line and becoming traitors. People died and soldiers who were prisoners in places like the Hanoi Hilton suffered terribly due to the actions of Tom Hayden. Tom Hayden was not a simple war protestor. He was not a spit-on-the-flag, burn-your-draft-card protestor. He understood that what he was doing was wrong, but he talked himself into believing he could give aid and comfort to the enemy, which even if it wasn’t his intention, was the end result of his actions. I looked right at him and called him a traitor.

CC: Did he look back at you?

GF: He looked at me. There was no expression.

CC: He did respond, however.

GF: Yes. He managed to defend himself.

Although Hayden did not speak only from a prepared text, he did say he had a game plan. He was a strategist by nature and considered what he was going to say to his colleagues. He lined up who was going to speak on his behalf, and what he’d say to the media and the larger public.

His speech did not take the luxury of two decades of hindsight to apologize for the actions of the 1960s. His speech was also memorable for the naked emotion.

“I opposed the war out of an honest rage,” Hayden said. He did not say his was a life without mistakes.

Then he went on the attack. He called Ferguson a narrow-minded bigot who was against everything Hayden stood for - women’s rights, minorities and the environment.

Hayden saw his effort in Vietnam as a byproduct of telling a larger truth, that 58,000 Americans were killed, tens of thousands more wounded, millions of Vietnamese killed and dislocated in an orgy of destruction. For him, the choices for which he was being made to answer narrowed down to going into the “heart of darkness to say we are being lied to, or keep equivocating and claiming we are in a noble cause.”

Tom Hayden: I remember thinking when the resolution was introduced that it was here we go again. This is the problem. You don’t get to control what you consider your agenda. I saw the Ferguson resolution as simply an attempt to once again divert attention from what I stood for, to discredit me, to discredit the 60s generation.

THE VOTE

Others stood up to speak. The passions of re-living America’s most controversial war, the politics that created a generation gap in America that resulted in bloody confrontations between cops and students, were bared. The comments were intensely personal, most of them directed at Hayden, but some going after Ferguson for refusing to let the issue rest.

Legislators from both parties approached Hayden to say they liked him, but they were going to vote against him. One of them even wrote a note saying much the same. Hayden says he kept the note somewhere in his files.

Gil Ferguson: We began a new count of the legislators and started to realize that moderate Democrats might break with Willie and vote with us. I told Willie as much. Holy shit, the color drained from his face. He wasn’t sure if Hayden was safe or not.

Hayden needed forty-one votes to survive. He received forty-one votes.

HAYDEN AND FERGUSON

On the afternoon we met with Tom Hayden he’d spent the morning at a meeting regarding gang problems in Los Angeles. He is still searching for solutions. He thinks the world can be rescued.

He has heart problems. There was a health crisis while he was vacationing with his wife and kids at the ranch of his former wife, Jane Fonda. He talked of death. He measured how many years his father lived, and how that mathematically plays out for the next generation.

The boy of divorced parents from a small town, Hayden has lived many lives - activist, revolutionary, politician, husband, father and grandfather. He can talk to his students of how he has always lived his life with a sense that there is a spirit afoot, a spirit that says all things are possible.

At the end of the day, however, he is not an impractical dreamer.

Hayden said, “At the beginning, our goal was to force the Kennedy Administration to enforce the regulation banning discrimination in interstate travel, or to desegregate lunch counters in the South, or to deploy Justice Department workers to protect people registering voters in the Black Belt. These were all reformist objectives that were powered by a fervor that could be called revolutionary or radical or it could be called religious. But there was always a practical side to it. The world was going to be changed in small steps, believe me.”

Gil Ferguson said without complaint that getting old is a terrible way for a strong man to die. He also said there were no regrets.

“I did the best I could to make a difference,” he said. “I did not retreat.”

Gil Ferguson often sailed his own boat on golden afternoons. He met everybody he wanted to meet, and went everywhere he wanted to go. Tarawa never left him, and at risk of indulging a hackneyed cliché, he took each day as a gift. He accepted that his life was closing to the timelines and efficiencies of a hospital.

His dear Anita was there, never tiring of his company, playful after almost 59 years of marriage, remarkably beautiful, and still making him a king of that little world remaining.

We took the last picture that would be taken of Gil. Not surprisingly, it was of Anita sitting on his lap. He kissed her when we were done, “I love you honey,” he said to her. Those were the final words we heard him say before we shook hands and said goodbye.

The following day, we received a message from Gil. “We can close ranks and respect those who opposed the war,” he said. “We can even forgive the cowards. But never, ever, will we forget the traitors, not even when they are gone and dead in their graves. Our country will never forgive traitors.”

Several days later Anita called late in the evening. “Gil is gone,” she said.

Tom Hayden called and asked if we interviewed Gil. We told him we saw him the week before he died.

“Isn’t that something,” Hayden said. “Well, God bless him.”