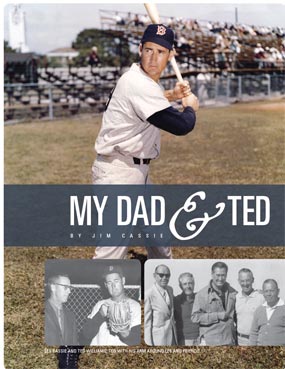

Written by Jim Cassie

Published Issue: Summer 2011

In the early years of the Great Depression, two kids from San Diego, a great guy, my father, Les Cassie, and a future baseball legend and war hero, Ted Williams, developed a close friendship.

They grew up during a time when two boys could get up early and find a day-long game at the then University Heights Playground, where foul balls ended up too often in a reservoir; or the Central Playground, a place neighborhood rivalries played out with an intensity that was largely unnoticed by most adults, since their supervision was not needed by boys playing baseball in the 1930s. It was a time and a place that no longer exists. Ted Williams would remember San Diego as ‘the nicest little town in the world.’ The home runs were hit into the yards of bungalows that were razed to make room for the newcomers. The San Diego of their youth was still somewhat rural, less than 200,000 people in a community where more than three million crowd today. The homes on Utah Street were affordable, if a bit run down, for a single mother. The people who bought the house at 4121 Utah Street almost fifty years after Ted’s mom bought it still boast that they also own the kitchen table on which Ted Williams signed his first major league contract.

Baseball

Baseball mattered to the boys. They played it every day with guys named Roy and Wylie and a big kid named March who was always chosen first. The professional teams they followed were all on the eastern side of the country and could be heard on the radio or read about in the morning and evening newspapers, and all of this was done in a smaller world and without ever knowing that television, let alone something like cyberspace, would be in anyone’s neighborhood.

Clearly, the common bond for these two friends was baseball. For Ted, it was hitting a baseball. Eventually, for my dad, it was teaching kids how to hit a baseball. And for me, it was a wonderful experience to see this long friendship up-close, all wrapped around the quietly optimistic decade of the 1950s. It was a marvelous time, although we didn’t appreciate it at the moment for all of its wonder. This story is about my dad, Leslie Robinson Cassie and his friend, Theodore Samuel Williams.

Records indicate that Ted’s given name was Teddy, for the first President Roosevelt, but later changed to Theodore. Ted’s mother, May, was of Mexican descent and seemed to find greater satisfaction working long hours for the Salvation Army than putting in time being a mother. She was once named San Diego’s Woman of the Year. It was complicated. Ted loved her. He said during a visit back to San Diego in 1992 that when he first started playing ball he finally had enough to eat. After that, he fixed up his mom’s house. Ted was really quite proud because he wanted his mother’s house to look good. It wasn’t always easy. Regardless, among the many honors Ted earned, he deserves to be recognized as the greatest Latino baseball player of all-time.

Both Les and Ted grew up in the North Park section of San Diego. They played on the same teams throughout their teen years. In September of 1932 they were among the 351 sophomores that entered through the High Tower of Herbert Hoover High School. Three years later, their yearbook boasted that amidst a battery of floodlights and flowers, 241 graduating seniors, strong, self-reliant men and women, were sent forth to meet the world. Out of the thousands of personal stories that must have existed for those kids, one of the few still surviving is that Ted Williams was so into hitting he actually carried a bat to class.

For whatever reason, Ted’s father was not around much. Ted ended up spending a lot of time with my grandparents. My dad was not a fisherman, but Ted and my grandfather spent hours on San Diego’s seaside piers trying to hook the big one. Both Les and Ted were skinny kids for their age. This is in part how Ted later got one of his more famous nicknames, The Splendid Splinter. He was also known as Teddy Ballgame, The Kid, and the Big Thumper.

For whatever reason, Ted’s father was not around much. Ted ended up spending a lot of time with my grandparents. My dad was not a fisherman, but Ted and my grandfather spent hours on San Diego’s seaside piers trying to hook the big one. Both Les and Ted were skinny kids for their age. This is in part how Ted later got one of his more famous nicknames, The Splendid Splinter. He was also known as Teddy Ballgame, The Kid, and the Big Thumper.

Not unlike teenage boys of every age, Ted and Les wanted to get bigger and stronger. A normal summer evening in 1933 was spent with the buddies shooting games of snooker, having a milkshake at the drugstore, and then jumping on the scales. Over the course of that school break neither of them gained a pound.

They both played organized baseball. Ted was brilliant, and quickly caught the eye of professional scouts. In 1935, he graduated early, in December, before the rest of his class, and signed a minor league contract with the independent San Diego Padres of the Pacific Coast League.

The following year, Ted Williams signed with the Boston Red Sox organization and was immediately placed in their farm system.

The following year, Ted Williams signed with the Boston Red Sox organization and was immediately placed in their farm system.

Ted had rarely traveled as far as the neighboring San Diego communities, let alone to the major league facilities in Florida. So, the boy who would become the great Teddy Ballgame and my grandfather, who was a carpenter for the San Diego School District, boarded a bus bound for Sarasota, Florida. During the trip, an already painfully skinny Ted became ill and the two of them were forced to stay a few days in New Orleans until Ted could be nursed back to recovery. That year was the last one where Ted Williams would not be one of the most famous people in America. Ted played well enough for the forgotten Minneapolis Millers in the American Association to be promoted.

On April 29, 1939, at the age of 20, Ted Williams played his first game in historic Fenway Park in Boston, Massachusetts.

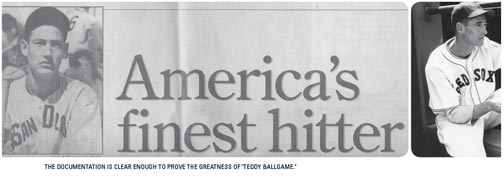

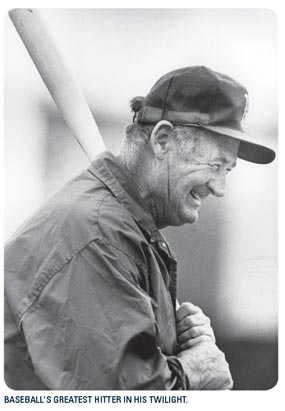

Over the next quarter century, Ted Williams would put together 21 Hall of Fame seasons. Those magnificent games were interrupted with four years of serving his country through two wars. He was a genuine All-American. As a boy, Ted told my dad and his friends in school that he wanted people to say he was the greatest hitter of all time. It all came true. Ted compiled a .344 batting average, had 521 home runs with 1,839 runs batted in. Also, while not known for being fast, he remains only one of three players to steal a base in four different decades.

Depression Boys

I recall one story told around our house demonstrating how tough things were near the end of the Depression and at the outbreak of World War II. After Ted signed his first big league contract, he bought a car and parked it in front of his parent’s house on Utah Street. Soon thereafter, the car was on jacks with the wheels stolen. His brother, who would lead a troubled life, yet was cared for and supported by Ted through a series of legal problems and health issues, a lifestyle leading to a premature death, had sold them for cash.

At the same time, his buddy, Les, long and lean and wearing his signature eyeglasses, entered San Diego State College. Baseball still mattered. He played on the baseball team and studied to be a teacher, a baseball coach and a sometimes scout. When the war broke out, his eyesight was so bad he was not aCCepted into the military. Instead, he took a break from his studies and went to work for the defense contractor that later became General Dynamics and labored as a draftsman building aircraft. Following the war, he joined a long line of soldiers and returned to SDSC.

Again, eligibility in place, my dad played ball. In the spring of 1945 or 1946, his San Diego State team was playing against UCLA in sparsely populated Westwood. It didn’t matter who won, but UCLA, like all the other schools, had an infielder who was getting started again after returning from the war. My dad pitched most of the game and gave up three hits to that Bruin without one of those balls getting out of the infield. The UCLA player was a multi-sports star by the name of Jack Roosevelt Robinson. Two years later, of course, the great Jackie Robinson would become one of baseball’s immortals and break the color barrier in the big leagues. He would also deservedly reach the hallowed Hall of Fame shrine in Cooperstown.

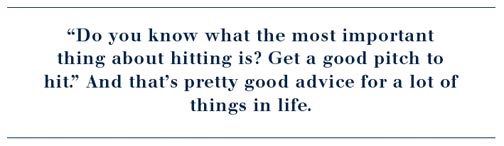

Ted brutalized American League pitching after the war and over the next five years led the league in every hitting category. The stresses of the real world intervened, however, in the form of the Korean War and on his way to re-writing the record books, Ted was recalled as a reservist after playing only six games in 1952. It is incredible to think of what his numbers would have been if Ted had not spent some key years of his career in a uniform other than baseball.

Ted brutalized American League pitching after the war and over the next five years led the league in every hitting category. The stresses of the real world intervened, however, in the form of the Korean War and on his way to re-writing the record books, Ted was recalled as a reservist after playing only six games in 1952. It is incredible to think of what his numbers would have been if Ted had not spent some key years of his career in a uniform other than baseball.

His war record has been well documented and his “ace status” as a pilot is a testament to his personal courage and his 20/10 eyesight. Williams said being a good pilot demanded athleticism. He taught others how to fly in WWII. He flew combat himself in Korea. Another big-leaguer, Yankee second baseman Jerry Coleman, was a pilot in a different squadron on a mission when Williams was shot down. Obviously, Ted survived. Coleman is the only major league player to face combat in both World War II and Korea. He would have a decent career as a player and spend more than twenty years as the announcer for the San Diego Padres. After flying 38 combat missions, Ted was released from duty and rejoined the Red Sox in mid-season, 1953. At that time, the Splendid Splinter was putting on the weight and muscle of his middle years. He was 34 years old.

Coach

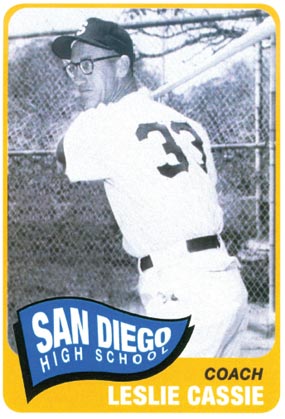

Throughout the late-forties and fifties, Les Cassie was a suCCessful coach at San Diego High School. Over 13 years, he produced tough teams that understood the fundamentals of the game. His coaching career included brief stints at his own Hoover High School and San Diego Junior College. His win-loss record was a staggering 200-28. He mentored gifted players, including Floyd Robinson who would play for the Chicago White Sox and Deron Johnson, who led the National League in runs batted-in (130) in 1965 with the Cincinnati Reds. Paul Runge, a fairly gifted catcher, played in the Houston organization but followed his dad as a major league umpire. Today, a third generation Runge is calling balls and strikes in the big leagues.

I recall coming home from the playground one day to learn that ‘The Thumper’ would be having dinner with us. My mother told me I couldn’t tell anyone Ted was there. If I had, she was concerned, aCCurately so, that the backyard would be filled with neighborhood kids. I remember the Russians had launched a satellite that day and we all were out there trying to see it. Ted had a rather salty vocabulary. No one used bad words in our house, so for me, it was like listening to the modern-day comics.

Ted always got around to talking about his favorite subject, hitting. In fact, the boy who left high school early wrote three books. One was called The Science of Hitting. He had charts and diagrams and it was something he understood viscerally and tried to share with others. I remember him asking me if the pitched ball looked like a “volleyball” coming at me. I said that it looked more like a “golf ball.” The next week I had glasses and have worn them ever since.

In 1957, my parents, my brother Tom, me and another couple, took a trip in a Buick Special. It was part business, but mostly pleasure. We spent three weeks in a car with no air conditioning visiting places like Joplin, MO, Chicago, Binghamton, NY, New York City, and any other place where there was someone in organized ball that my dad had played with or coached. The best stop was Boston. Ted always lived in a hotel. It was there I met Bobbi Jo, his daughter by his first marriage. She was my age, maybe a bit older. I remember we needed to run everywhere to avoid his fans. It was amazing. It was on this trip that I had my first ride in a taxi. Bobbi Jo was fearless and immediately got on the portable radio to talk with the dispatcher, who she seemed to know. She was something.

Ted loved the outdoors. He was allowed to keep his hunting skills sharp during the season by shooting pigeons that landed on the infield at Fenway. He did agree to do this on game day afternoons when the fans were not around. As gifted a fisherman as a baseball player, he lived in the Florida Keys during the off season. Sometime near the end of his career, a hurricane hit the Keys and many of the items he saved from his playing days were lost. I came home from school one day and there was a large trunk in the garage. It was filled with Ted’s old uniforms, hats, gloves, baseballs, bats and more. He had shipped what remained of his collection to our house. I recall thinking this is just a bunch of old stuff. I was wrong. Just before Ted was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1966, the trunk was shipped to Cooperstown.

Last

Ted’s last season was a memorable one. In 1960, at the age of 42, he hit .316 in 113 games. In his final trip to the plate, he hit one out. He touched home, ran in the dugout and went directly to the clubhouse. He later said he wished he had stepped out of the dugout and tipped his hat to the Bosox fans. His relationship with them was an uneasy one, but Tom Yawkey, owner of the team, respected Ted so much that in the latter part of Ted’s career Yawkey sent him a blank check with his contract and allowed Ted to fill in the number.

One of my last recollections of my dad with Ted was at a dinner in San Diego that was sponsored by Sears. Ted had signed a deal to put his name on fishing rods, reels, guns, baseball gloves and anything else that would help sell their merchandise. During the meal, the president of Sears asked Ted how he liked their new line of fishing gear. Ted abruptly said something to the effect that he just has his name on it, he doesn’t use it. It deflated the Sears man.

From 1969-1971, an aging and increasingly irascible Ted managed the Washington Senators and led them to their only winning season with that name and in that city. I remember visiting with him during a series with the California Angels. He was swarmed when he went through the hotel lobby, but he really didn’t want to stay in his room. We went to the ballpark. It was mid-afternoon and he asked the Angels to put a rocking chair in centerfield prior to the night game. Soon Jim Fregosi, the Angel star at the time, and several of the Angel players were talking about hitting with ‘The Kid.’ That night, the Senators beat California 2-1 in 15 innings. My wife at the time thought it lasted an eternity, and when asked by Ted how she liked the game, told him, “All you guys do is spit and scratch.” Imagine that.

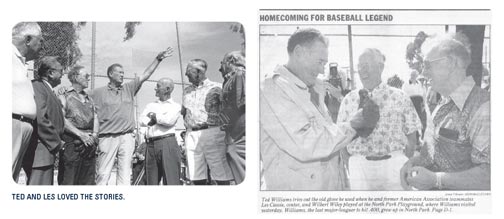

My dad and Ted talked over the years on the telephone. They did manage to get together for a mini-reunion at their old playground during a celebration in San Diego where they named a freeway after Ted. In 2000, Les would be inducted into the Coaching Legends at the San Diego Hall of Champions. Ted summed up their friendship. “You know,” he said, “I’ve always thought of Les as my brother.”

I was lucky. Les was my dad. Every time I went back to San Diego and someone heard my name they would ask me if Les Cassie was my dad. I’ve said yes a few times in my life. I’ve never said it with more pride than I would say it at those moments. I loved him very much.

The End

The end for Ted was unfortunately bizarre. Shortly after his death in 2002, his son, John-Henry, a product of his second marriage, produced a family pact that apparently Ted had signed saying he wanted to be “suspended by cryonics” at a life extension foundation in Scottsdale. Bobbi Jo, still tough like her dad, sued, saying her father wanted to be cremated. That was what Ted told my dad. He even added that he wanted to have his ashes scattered over the Florida Keys to join a favored, previously departed dog, Slugger.

The theory was that John-Henry was marketing his dad’s reputation and wanted to sell his DNA as a possible winner. At one point, my dad told John-Henry that “nobody has more of Ted’s DNA than you and it doesn’t help you hit a curve ball.” Ted’s boy would not enjoy the benefits of his marketing skills for long. He died from leukemia a few years after Ted, at the age of 35.

Les

My dad passed away in May of 2008. My mother joined him in October of that year. They are gone, but my brother and I were left with a locker room full of good memories. And this one is as good as any. On our trip in 1957, after visiting with Ted, we went with him to New York where they were playing the Yanks. My dad was a scout at the time for the Yankees, so Tom and I got to go into their clubhouse and see the likes of Bobby Richardson, Hank Bauer, Mickey Mantle, Moose Skowron, and Yogi Berra. There was also another San Diegan in the clubhouse – Don Larsen; the only man to pitch a perfect game in the World Series (1956). What a treat. Our seats that day were directly behind home plate in the first row. One inning, Ted led off and said something to the catcher, Yogi, who turned and gave a quick wave to a woman in a red dress. It was my mother and she nearly fainted.

I still picture the setting today: dinner on Austin Drive in San Diego with Ted at the table and Ted says to Tom and me, “Do you know what the most important thing about hitting is? Get a good pitch to hit.” And that’s pretty good advice for a lot of things in life.

Postscript: On an early spring evening in 2009, I had the opportunity to meet Don Larsen and his wife in Sacramento. We chatted about mutual acquaintances we shared because of my dad. Larsen had graduated from Pt. Loma High School in 1947. Of course, the story always takes a turn. In 1998, another Pt. Loma High alum, David Wells, pitched a perfect game in Yankee Stadium. And who was in the stands? Don Larsen.

California Conversations (CC): Did you ever spend any time with Ted Williams?

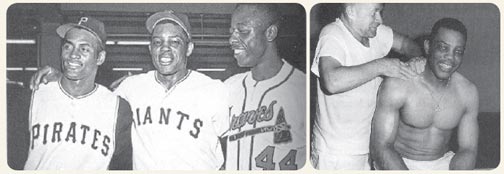

Willie Mays (WM): Ted was a good friend of mine. We would see each other at baseball events after we retired and he was always very friendly to me. And I guess that was not the case with everyone.

CC: Did you talk about hitting?

WM: No, I never talked hitting, or even talked about playing baseball, with Ted. I never really do when I’m talking to baseball people. Whatever anybody’s done, I’ve already done it.

CC: When did you first realize that you could hit the ball better than anyone else?

WM: I was 12. I didn’t play little league ball. I was already playing on a semi-pro team in my hometown near Birmingham, Alabama. I could hit the ball better than guys anywhere around my age, and I was playing with grown men. I was playing on teams with my dad.

CC: Your dad had a great nickname?

WM: Yes, he was called Cat Mays.

CC: Was he as good as the Say Hey Kid?

WM: I don’t know. (Laughs) I don’t judge. I don’t do that. I don’t judge people by what I do. I think the fans have to do that and not me.

CC: What was the biggest difference between playing in New York and San Francisco?

WM: Nothing. It’s just baseball. You catch the ball, you throw the ball, you hit the ball.

CC: Would the Dodgers and the Giants hang out when you all worked in the same city?

WM: No. When the game was over they went their way, I went my way.

CC: Did you live in New York City?

WM: Yes, I lived on A Street, right by La Guardia Airport and then I lived in New Rochelle on North Street. That was back in 1956-57. Then we moved to California in 1958 and San Francisco has been my home ever since. I like California.

CC: When you were in the Army, were you ever concerned that you would lose a step or that you wouldn’t be able to come back and play baseball?

WM: No, I really didn’t think about it. The Army was good for me. I grew up, I got stronger. I played five days for the Army and two for myself in a City League. I didn’t want to go. I made the best of it. I might have had another 60 or 70 homeruns if I hadn’t gone into the service.

CC: You would have broken Babe Ruth’s record?

WM: Yeah, but still that wasn’t important. It’s just a number to me. My father and I used to talk and we discussed that you have to be in the top five of everything important and if you look at my record you’ll see I’m in the top five of stolen bases, hits, knocked-in runs, home runs, all kinds of stuff. Top five. Think about that. A lot of guys are good hitters or good fielders, they’re good base runners, but they’re not in the top five of many things, maybe just one thing. I played 150 games or more for 18 or 19 years, and that, to me, is a lot of games. I led the league in stolen bases four years in a row and then I quit running. I only stole when I had to.

CC: 338 stolen bases?

WM: I could have stolen 450, probably 500 if I wanted to. Again, those are just numbers. They didn’t tell me they were going to keep records on that kind of stuff.

CC: Can you teach hitting or do you just have to have that skill?

WM: I can tell someone what to do and how to do it. We had a kid, a third baseman, Matt Williams, and Matt couldn’t hit a breaking ball when we first got him. We taught him.

CC: When people talk about the great hitters…

WM: Hitting? That is only one aspect of the game. It’s not all about hitting. I’d rather play defense than hit.

CC: Was defense more fun?

WM: It is the key to playing baseball. If you can play good defense and you can score one run then they got to score two. You see a lot of teams with good offense, but the offense is not enough.

CC: You won twelve gold gloves.

WM: They didn’t start that award until I was in the league for five or six years. I was the captain on the field and I would set our team up depending on where the pitcher was going to pitch. If he throws the ball in the same area and you know the batter, you will have an idea of where he is going to hit it. The great catch most of the time is not having to make a great catch. It is being where you are supposed to be. Like people have computers now, I was computing in my head. I had to know everything about every club, every hitter.

CC: Who chooses the captain?

WM: On the Giants, the manager did. Alvin Dark did that for me. We played together when he was a shortstop in New York and if the pitcher was throwing a breaking ball, Alvin put his hands behind him to let me know it was coming so I could expect to catch a ball in the gap. He was good.

CC: When you are at the plate what does the ball look like when it is coming toward you?

WM: I could see the seams on the ball. Maybe that’s why my eyes are bad now because I had to squint to see what was coming all the time. I could see it all.

CC: You’ve said the famous Vic Wertz’ over-the-shoulder World Series catch was not your greatest catch.

WM: I made a lot of better catches than that, but it was the most publicized one. In 1954, the World Series was done in four games so they had to pick a highlight I guess and they picked that one.

CC: What would you have done if you had not been a baseball player?

WM: I don’t think I wanted to do anything else. My dad would never let me go in a coal mine, he never let me work, I never had a job. I actually had a job for 3 hours one day and I quit it because it interfered with my game.

CC: What was the job?

WM: Washing dishes at a restaurant. It was not a career I wanted.

CC: I hear you are a pretty good golfer?

WM: That was after baseball. I got down to 4 when I could play every day.

CC: Do people still come up to you and say “Bye, Bye Baby?”

WM: No (laughs). That was Russ Hodges. He was a great guy and a great announcer. They play ‘Bye Bye Baby’ at the ballpark now. I had two batting coaches, Lon Simmons, the other announcer, and Russ Hodges. They could see me changing my swing and they’d call me and say you changed and I’d go home and look at a film and find out they were telling me the truth.

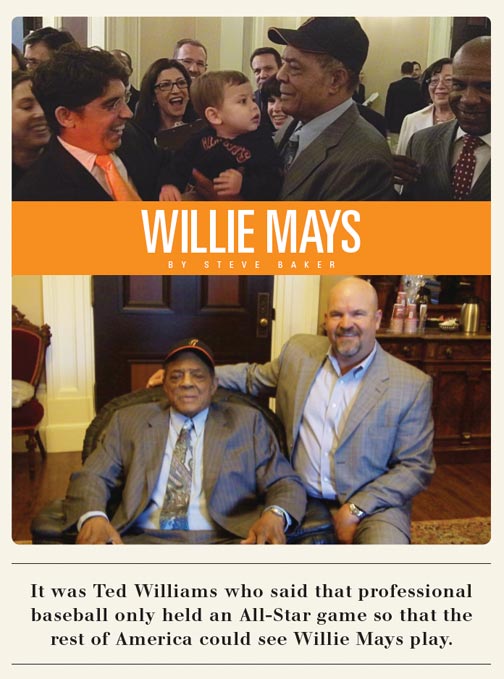

CC: The President pro Tempore of the Senate, Darrell Steinberg and the Speaker of the Assembly, John Perez, wrote a resolution calling you the greatest baseball player of all time and they presented the resolution to you on the floors of both their houses on your 79th birthday.

WM: It was a great honor, one of the great honors of my life. I was very proud to be there. (Laughs) And they got the resolution right.

CC: Can you help me get tickets to the Giants?

WM: (laughs) Call me. I can work something out.