Written by Randy Perry & Terence McHale

Published Issue: Summer 2007

|

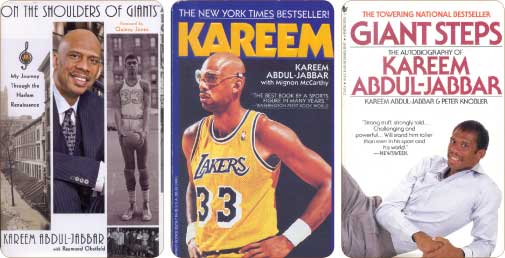

The autobiographical books, “Kareem” and “Giant Steps,” are filled with the kind of revelations usually reserved for close friends and trusted confessors. The detail, especially in “Giant Steps,” is unexpected from someone with a reputation at the time for being reticent, although the honesty makes for good reading and the reflections keep your attention.

His newest effort is less about him.

“On the Shoulders of Giants” is a well-reviewed visualization of a politically vibrant, artistically charged period between 1920 and 1940 in Harlem. The Black Renaissance is what he calls it, and Abdul-Jabbar, eschewing the Disneyfication of black culture, takes the reader through a lively trip into the neighborhoods of a place long gone and, thankfully, not forgotten.

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar has been a noted American figure from the day he started as the freshman center on the basketball team at UCLA more than forty years ago. Freshmen players were not eligible to play on the varsity then and were relegated to smaller gymnasiums against mostly junior college squads. Abdul-Jabbar, then known as Ferdinand Lewis Alcindor, Jr., was the centerpiece of a team that humbled their own varsity - the varsity was number one in the country, yet only the second-best team on the Bruin campus.

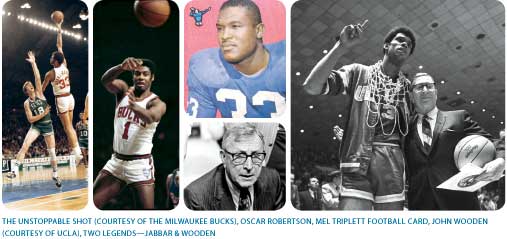

Kareem’s arrival in Westwood from Power Memorial High School in New York meant John Wooden would find his place in history as more than a coach who won two championships after sixteen years of running the bench. A fine coach, and a smart recruiter, Wooden would instead be the architect of a sports dynasty that challenges the Yankee and Celtics legends.

UCLA has eleven National Championships; Kareem was responsible for three in a row. He was so dominant that beyond winning the Most Valuable Player Award every year, the rules of the college game were changed to take away the dunk and make it more difficult for Kareem to score. Of course, nothing could be done to interrupt the poetic grace of his unstoppable sky-hook.

|

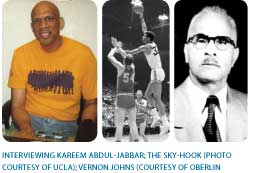

California Conversations met with Kareem Abdul-Jabbar in a small room at a modern business building. We arrived twenty minutes early. Abdul-Jabbar did not make us wait.

He needed to duck his head when he entered the room. There were no surprises. He is seven feet two inches tall and looks to be close to his playing weight of 265 pounds. He was wearing a gold tee shirt and tight jeans. There are only a few in his generation who can wear either comfortably. He shakes hands and sits down. Kareem is completely bald. The mustache and tickler he has worn for decades are sparse. Except for filling out a bit, his face has not changed much since we first saw him as a young man in sporting magazines.

Kareem leans forward when he sits down. His long arms lock between his legs and he waits for the question. There is nothing impatient in his manner. In one of his books he said he’d been considered once by interviewers to be taciturn and given to providing monosyllabic answers with no embellishments. None of this is true in our meeting. He is not ebullient, but he is pleasant and unrushed.

We spoke first about his early Hollywood involvement. His days as an actor are most memorable from his self-mocking role as a co-pilot in the spoof, “Airplane,” and the fearsome martial arts adversary in the Bruce Lee film, “Fists of Fury.”

There is much more. In 1994, Kareem produced a movie about the early civil rights activist, Vernon Johns. The film explores the life of a man born in the first generation after slavery, a life that was framed and changed by the indecency of Jim Crow laws and ended at the onset of the modern Civil Rights Movement in 1965.

California Conversations: Why were you drawn to Vernon Johns?

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: I felt Vernon Johns was important because he was Martin Luther King’s mentor. He was the first to explain the pertinent issues with regard to human rights and equal opportunity that Dr. King espoused throughout his lifetime. Dr. King would never have understood the depth of those issues if it hadn’t been for Vernon Johns. Also, nobody knows Vernon Johns anymore so it was a great opportunity to inform people interested in Dr. King’s life and the history of the Civil Rights Movement.

CC: He was virtually self-educated.

KAJ: Just about, yeah, because the school system in the South, where he was from, was not about getting people of his color to the top of the educational heap. He got there by himself.

CC: Interesting how he learned Greek to pass the entry tests for college…

KAJ: And Latin. He was just an extraordinary human being. Even without regard to the issues he was involved with, he was very determined.

CC: Does this country still produce Vernon Johns-type people?

KAJ: I don’t have my finger on that pulse, so it’s hard to say. I hope we still do. Those are the people who make a difference.

CC: How close was his mentoring of Martin Luther King?

KAJ: He was directly involved in the public education of Martin Luther King. King even ended up taking over for Vernon Johns at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. Both of them were great preachers in the Southern tradition.

One of the final stops in Johns’ career was becoming the 19th pastor at a small church in Montgomery, Alabama, that was originally called the 2nd Colored Baptist Church - a youthful King - only twenty-five when he took over the pulpit - was the 20th pastor.

CC: Any differences in style?

KAJ: Johns was hard on his own, on the people who were supposed to be on his side; he was as hard on them as he was on the people with whom he had issues. He couldn’t compromise. He wanted the people in his own congregation to make a statement that they could not afford to be complacent. They could not be comfortable and hope they could keep their heads out of the storm while the storm rained on everyone else.

CC: Did he pay a price for his toughness?

KAJ: He alienated people, even his own family. His children were afraid of him.

CC: You’ve written about the Harlem intellectuals between the two great wars needing to break with Booker T. Washington...a generational shift...did the same thing happen with Martin and Vernon Johns?

KAJ: Martin toned down Vernon Johns’ approach. Martin actually had it easier than his mentor. Vernon Johns was totally not going to compromise.

CC: And at the end, does it matter that Martin did not bring Vernon Johns, an old man then marginalized by his many confrontations, to the March on Washington?

KAJ: Dr. King understood Vernon Johns wanting to see meaningful change and his belief there was only one way to cause this meaningful change and that was to confront the issues head-on. You need to be confrontational while maintaining the moral high ground. I think the relationship was good between the two of them, but again, Martin had it easier than Vernon Johns, an easier personality and people were more willing to embrace progress.

CC: The words of Vernon Johns survive as one of the first black preachers to insist on publishing his sermons.

KAJ: People forget that even great black preachers had a difficult time because no one cared about what they had to say. Probably the only black preacher in the country with any access to the national news was Adam Clayton Powell, Sr., at the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Manhattan. And if his church hadn’t been in Manhattan he wouldn’t have received any attention either.

CC: How difficult was it for you as a producer to be able to sell the Vernon Johns story?

KAJ: It was easy because James Earl Jones (Academy Award winning actor for “The Great White Hope” and the voice of Darth Vader) wanted to do it.

CC: Your involvement wasn’t enough?

KAJ: It’s not easy to make that kind of shift from one career to another. James Earl Jones wanting to do the film helped make more people listen. He took a couple meetings with us and was totally committed. He had done a piece on the nightly news, just a little snippet on Vernon Johns’ life, a confrontation with a sheriff, I believe, or a police official in the South.

CC: Did the Vernon Johns experience encourage you to research and write history?

KAJ: It helped, sure. It made a difference but I’ve always had an interest in history.

CC: You wrote a book called “Brothers in Arms” about the 761st Tank Battalion in World War II. It was evidently prompted by meeting someone, a gentleman who was one of the ...

KAJ: Yes, actually he was a good friend of my father. They were police officers together; Leonard Smith. I’ve known Leonard Smith from the time I was 6 or 7 years old. I knew him as one of my dad’s buddies who was a cop. Then, in 1992, I saw a documentary on the 761st Tank Battalion and he was in it. All of a sudden I realized who he was. I’d known him my whole life and didn’t realize the role he played in winning the war.

CC: The 761st was part of George Patton’s army?

KAJ: Yes.

CC: Was there an idea initially in Patton’s army that the 761st wasn’t capable?

KAJ: Patton had a negative idea about black troopers. He was forced to deal with the 761st Tank Battalion because they were the only well-trained battalion remaining that hadn’t seen any action, and he desperately needed bodies. In 1944, after the invasion of Normandy, there was a manpower shortage in the American army and the only people that had been trained who were not in combat units were black soldiers. Many of them were already in Europe. They didn’t even have to transport them over there. So, a lot of people went from service units into combat units and they were able to replenish Patton’s army.

CC: Your book mentions that most of the tank units would serve for a month or two and then have a break, but the 761st ended up serving two or three times longer. Was it the manpower shortage or was it because they were treated differently?

KAJ: They were treated differently. Any other unit would have been given some form of relief while they went from one hot spot to another.

CC: And how did Patton end up feeling about them?

KAJ: I think Patton finally appreciated them. Certainly some of the people they fought for definitely appreciated them. A general, other than Patton, went out of his way to get them the commendations they deserved. He would put the documents together and send the packets in. Then the paperwork would get lost in the bureaucracy because once they saw it was black soldiers, curious things happened. The general did all he could to see they got recognized because he realized how many of his boys’ lives they had saved, and he was very appreciative.

CC: So, did they get the recognition ultimately?

KAJ: (smiles) President Clinton, yeah.

CC: They were the original Black Panthers?

KAJ: Yes, they were. I believe that some of their children, who were living in the Bay Area, took that name because of how much they admired their dads for fighting in the 761st Tank Battalion.

CC: How many were there?

KAJ: There were 660 tankers in the 761st when they left Texas to go overseas.

CC: And how many came home?

KAJ: I don’t have the numbers now but between the dead and injured, the casualty rate was almost 50%.

CC: Their big moment was at the Battle of the Bulge?

KAJ: Yeah, certainly the most memorable or most noticed moment. Antwerp was the goal for the Germans, but there was a town that controlled all the roads and that’s where they and the 17th airborne did extraordinary work. They eliminated any possibility of the Germans controlling the roads to Antwerp. If the Germans had controlled the corridor to Antwerp it would have kept the Allied Army offshore and prevented them from getting supplies to the people who were trying to cripple Germany. Antwerp was the perfect port to service the attempt to enter the German heartland.

CC: The black soldiers perform admirably and the war ends…

KAJ: They were heroic…

CC: You allude to it in “Brothers in Arms” and in your “Black Profiles in Courage” but in your latest book you talk directly about the fact that after the war the black soldiers had different expectations.

KAJ: They realized that in coming home there was one issue that hadn’t been dealt with and that was how they were treated here in America. They wanted first-class citizenship. They felt they’d earned it. They had the determination of people who one way or another supported and upheld the war effort that saved America, and they could not go back to being treated as they had been before.

CC: ...the burgeoning of the Civil Rights Movement?

KAJ: Right. I’m convinced it began with people who were involved in the war effort.

CC: Is all the research you do a chore?

KAJ: I enjoy it.

CC: Are you surprised by the positive reaction to your writing?

KAJ: I don’t know. I’m pleased, but it’s not why I do it.

CC: Is writing a grueling process for you?

KAJ: It’s fun when you have something to say. If you don’t know what you want to say, it’s got to be murder.

CC: When you have a project going, do you write every day?

KAJ: More or less. I figure out the structure of how to frame what I want to say. I need to keep it coherent and make sure it holds together and people can understand the story I’m telling. You just can’t come out with a kernel of what you want to say and leave it there. You have to show the rationale for the facts that lead up to your conclusion.

CC: How much do you write now?

KAJ: Well, I don’t have a project going now. I don’t write unless I’m on a project. On “Brothers in Arms” I was so consumed with the text that I realized after the book was published I didn’t get the pictures and maps in there that I wanted. I was concentrating completely on the text and making sure it was complete and it would withstand scrutiny.

CC: Does writing a book take over your life?

KAJ: I need to do other things at the same time because when I go away from a project and come back to it, I’m fresh, my energy is renewed.

CC: You’ve worked with co-authors on your books.

KAJ: Yeah.

CC: It’s interesting that you chose different co-authors for each of the books.

KAJ: The first couple I didn’t choose them. It was only recently that I got to pick the people with whom I work.

CC: So the publishers chose…

KAJ: Yeah, they did.

CC: Did that bother you?

KAJ: No. No. My very first book, I’d known my co-author since high school.

CC: That’s “Giant Steps.”

KAJ: “Giant Steps” yeah. Peter Knobler. We’re still friends. But, the rest of the co-authors I didn’t know until I decided to do the project.

CC: In “On the Shoulders of Giants” there are chapters that specifically have your byline.

KAJ: Those were chapters in which I did not collaborate. They were all mine and they were chapters my co-author said he didn’t know anything about and thought I should get special credit.

CC: Your first book is very candid - surprisingly so. You write in a later book that you had doubts just before its release. Do your kids ever say, Dad, couldn’t you have held a few things back?

KAJ: No. I wanted to be truthful.

CC: You write poignantly about the emotional distance from your father…

KAJ: He was very quiet. My dad was a very reserved person and I think his career as a police officer helped shut him down because he saw a lot of bad things. We became closer when I moved to Los Angeles.

CC: You were an only child.

KAJ: Yes.

CC: Are you close to your own five children?

KAJ: Oh yeah, I am. I went the extra miles, whatever it took to make sure I kept the lines of communication open with my kids. They are good people. I’ve been very blessed.

CC: Are you a grandfather?

KAJ: (smiles) They won’t get married. I guess they watched my life.

CC: In your twenties you were very close to Hamaas Abdul-Khaalis? He taught you Islam...huge figure in your life?

KAJ: For a while, yes. But he got bent.

Several members of Abdul-Khaalis’ family were slaughtered by a rival Muslim sect in a home owned by Jabbar. Abdul-Khaalis himself ended up in prison after instigating his own hostage taking response.

CC: He gave you your name?

KAJ: Yeah.

Kareem initially changed his name to Abdul-Kareem. At the prompting of Abdul-Khalis, he changed his name to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, meaning noble and generous, servant, powerful.

CC: Abdul-Khaalis persuaded you which girl of two in question to marry?

KAJ: Which choice to make.

CC: You’re very honest about your growth as a human being.

KAJ: I’m very glad that I got to the part that I felt confident enough to make my own decisions.

CC: You learned Arabic to get to the true source of Islamic study material?

KAJ: Right.

CC: Do you still pursue it with the same ardor?

KAJ: Not maybe with the same ardor, because I’ve become a lot more secular, but it is still my moral foundation and it is still what I believe in.

CC: As I ask these questions it makes me wonder if you’ve had any real privacy since your days at UCLA?

KAJ: It goes back further than that. When I was in grade school and already over six feet tall my choir class went to Jack Dempsey’s Restaurant, and Dempsey made a point of coming over to meet the tall kid from the Catholic school.

CC: Did that bother you?

KAJ: Dempsey was great with kids. But I knew I was being treated differently.

Abdul-Jabbar was 6’10” tall as a high school freshman at a time when Bill Russell was dominating professional basketball at 6’9”.

CC: At this point in your writing career can you choose who you want as a co-author?

KAJ: They let me have a strong say in choosing with whom I want to work. And I like having a co-author because it allows me to keep pursing other interests.

CC: You said in the past that had you not been an athlete you would have been a history teacher.

KAJ: When I left UCLA I had a degree in history and a minor in English. At first I was an English major, which leads to writing, so I’ve really built on things I’m passionate about. I thought of being a journalism major in college, but UCLA didn’t have a school of journalism.

CC: UCLA didn’t have a school of journalism?

KAJ: No, but they had a great English department.

CC: Your first move toward journalism took place when you enrolled in a youth journalism project called HAR-YOU-ACT run by the brilliant John Henrik Clarke?

KAJ: Yes, although Dr. Clarke did not run the program after putting it together. It was actually administered by a lot of different people. The guy who was in charge of the journalism workshop was named Al Calloway.

CC: Any relationship to Cab?

KAJ: (smiles) No relationship to Cab, but he led the workshop and ran it like a publisher. He taught us how to investigate a story and write about it. He was firm, and said, all right, we need to put out a newspaper every week. And it was real writing. We had to write about things that happened and we observed.

CC: At 17, you get a genuine press credential. I mean, that’s pretty heady stuff.

KAJ: Yeah, it was.

CC: You went to a press conference for Martin Luther King?

KAJ: I did. Being the tallest in the room I took my usual position in the back of the group. I thought it was a big deal being there. I remember one guy I recognized, the local broadcaster - there were some other recognizable guys I’d seen on television.

CC: Was this the first time you’d seen Dr. King?

KAJ: Yes, it was. I’d seen him on television. I’d observed different moments in the Civil Rights Movement on television.

CC: And you dared to ask a question?

KAJ: Yeah. I asked him for his assessment of Dr. Clarke’s performance in setting up the Har-You-Act program...he said it was important. He said he felt it was probably successful.

CC: Dr. King at this point is 34-35 years old and has less than four years left before his murder. How often do you run into him over the years?

KAJ: I never saw him again.

CC: Were there other political figures that influenced your life?

KAJ: Adam Clayton Powell, Jr.

CC: The congressman?

KAJ: Right. I used to live in his district. We moved from Harlem to the northern end of Manhattan, so I wasn’t technically in his district anymore, but I spent so much time in Harlem.

CC: Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. is another one of those extraordinary figures of American politics that people don’t know anymore.

KAJ: That’s true, unfortunately.

CC: What was it like? Did you see him around?

KAJ: Yes. I would see him around the city and people surrounded him...they wanted to touch him. He spoke at UCLA my senior year. He was an incredible guy and very knowledgeable about what was going on in the world. Plus, a sidebar, he knew all the bright lights in the Harlem Renaissance. Fats Waller learned how to play the organ at his father’s Abyssinian Baptist Church organ because Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. would let Fats in when everybody was gone.

CC: Adam Clayton Powell Jr. got into trouble over campaign funds and was deserted by the people who supported him in Washington, right?

KAJ: His base in Harlem was assured. They couldn’t get rid of him. They tried, but the people in Harlem figured if those people in Washington didn’t like him, he had to be doing something right.

CC: Do you remember him heroically?

KAJ: Yes, absolutely.

CC: A significant, positive figure in your life?

KAJ: He was important. He was critical about the political parties in America, and when he went overseas everybody thought he would make anti-American comments. He didn’t. He said America was not perfect, but it was the best chance the world had for a truly free society. Then when he came back to Congress they gave him a standing ovation and appreciated the fact that he was a loyal American. He was very charismatic, and he loved the attention.

CC: Did you get to know him personally?

KAJ: I did speak to him. I didn’t get to know him. He was married to Hazel Scott, a great jazz musician and I was familiar with her music.

CC: He wasn’t married to her at the end though, was he?

KAJ: Not at the end. He had a number of wives.

CC: He was a fabulous character.

KAJ: Yeah, he was.

CC: In the book, “On the Shoulders of Giants” the way you paint Harlem, I felt like I was walking down the street.

KAJ: Well, thank you. I’m glad you enjoyed it.

CC: I loved the way you break down the different neighborhoods...would Adam Clayton Powell be one of those striving for better things who lived in the ‘Strivers’ section of Harlem?

KAJ: The Abyssinian Baptist Church was right across the street from ‘Strivers’ but I don’t know exactly where he lived.

CC: The Harlem Renaissance...the incredible figures...seminal political movement, great writers, the music...you mentioned Fats Waller...Fats was dead at 39.

KAJ: Yeah, that was a shame. He died during the war.

CC: You write a couple of times about hearing your dad - who was trained at Julliard - playing Jazz when you were still in your Mom’s womb and your Mom taking you to pick him up on Sundays for a family breakfast when he got done playing and, of course, meeting Thelonious Monk and the importance of John Coltrane. I guess I’m leading up to asking if Jazz is dead.

KAJ: Jazz has never gone away, particularly worldwide. They love it in Europe and Japan, which assures it a long life, but it does not have the following one would expect in America. Dance took hold with the emergence of R&B, and the importance of virtuosity on a musical instrument got lost.

CC: Is a political renaissance possible with hip-hop like the one that accompanied Jazz in Harlem?

KAJ: There is no political message in most hip-hop. It’s just the latest flavor of popular music in the black community. There’s no time or interest in becoming a Charlie Parker or a Miles Davis.

CC: You write affectionately about Miles Davis - all time favorite jazz musician?

KAJ: Certainly one of them. It’s hard to name one, but certainly one of them.

CC: You were nice to Miles in your writings though because he did go through a period of decline.

KAJ: Yes, he did...I think what he achieved vastly outshines any of his failures. He didn’t let his failures...he didn’t stick with his failures. He got himself back physically and through his fifties and sixties was the cutting edge of what Jazz is all about. I think that is a lot more important than the times when he was down. My dad was a corrections officer for six, eight months before he became a policeman, and he saw Miles at Ryker’s Island. Miles was no angel, but once he cleaned himself up he stayed that way and took care of himself.

CC: Your life was changed by HAR-YOU-ACT and the mentoring you received there from Al Calloway.

KAJ: Yes.

CC: It might never have happened if your high school basketball coach had not used the ugliest of racial epithets to motivate you. Your response was to cut short a summer basketball camp and attend HAR-YOU-ACT…

KAJ: Yes.

CC: Coach Donahue…

KAJ: Coach Donahue was someone...he had a bad moment, okay, he made a mistake. He overreacted, I think, because we had an important game to play, and I wasn’t playing very well. He used the wrong word to describe the way I was playing. But, Coach Donahue was an extraordinary man. What I learned from him about the game of basketball, what I learned from him about being a good citizen, has been with me my whole life. He’s an extraordinary man.

CC: Did you love him?

KAJ: Absolutely.

CC: Looking back on it now, you’re quieter, but this was a defining moment in your life.

KAJ: It was, because at that point I had nothing but positive feelings about Coach Donahue and then using his choice of words, he made me think what’s behind it all? It was like a real betrayal of trust. It certainly disillusioned me.

CC: To the point that you were going to leave Power Memorial High School?

KAJ: Right. I thought about that for maybe a day or two.

CC: Did he ever apologize?

KAJ: Yeah, he came by and spoke to my parents about it. He in no way was a racist, and he wasn’t trying to hurt me. He was trying to push my buttons; he just went too far. It had a devastating effect on the trust I had for him because I really trusted him and appreciated him and learned a lot from him.

CC: Your next coach, of course, was John Wooden at UCLA. In your books, Coach Wooden is taciturn. Did you ever have an in-depth conversation with him?

KAJ: Oh, yes, certainly. Of course, Coach Wooden’s whole idea was that he wanted us to get our degrees and learn how to be good citizens.

CC: Great man?

KAJ: Extraordinary man. Extraordinary American.

CC: One of the great men you’ve met?

KAJ: Yes, absolutely. Yeah, I mean he was someone all Americans should know about because of what he stood for and what he achieved as an athlete and as a human being, certainly as a teacher and a coach.

CC: I learned from your writing that he was a great athlete at Purdue and played in the early days of professional basketball.

KAJ: He was, I think, for a while there, the highest paid professional basketball player in the country.

CC: Did he ever mention to you when you were at UCLA that he played basketball against the all-black Harlem Rens?

KAJ: No. For him that would have been talking about things that happened thirty years earlier that nobody knew anything about. We talked about it when I got older and he told me about getting to know Fats Jenkins, the great guard for the Rens, and following the Indianapolis Clowns Negro League team because there was no major league baseball in Indiana.

CC: Would Wooden invite you to his house, would he socialize with his athletes?

KAJ: Yes, and so would his family, his wife, and even his grandchildren.

CC: Did you stay close to him?

KAJ: Yeah, these last couple of trips to the hospital really bothered me. He’s still very sharp. The last time I saw him, we started talking about old-time teams.

CC: Did he say that yours was the best team?

KAJ: No. (laughs) We were talking about baseball. (Baseball was Abdul-Jabbar’s first love.) He has such a broader view of it because he was born in 1910. We had a little dispute about who would play first base.

CC: Who would play first base?

KAJ: On Coach Wooden’s team?

CC: Yeah.

KAJ: Lou Gehrig.

CC: Who would play first base on your team?

KAJ: Stan Musial.

Mel Triplett is a forgotten running back who played for a few years in the late 1950s for the New York Giants. In sports trivia he is important because he was a favorite of Kareem’s. Triplett wore number 33. It is the number Kareem chose in high school and has worn ever since.

CC: Talk a little basketball?

KAJ: Okay, if you want to.

CC: Did you ever play one-on-one against Bill Walton?

KAJ: No. (smiles) We never did.

CC: C’mon, just the two of you guys getting together, never played?

KAJ: No. Really. I met him. I was in Los Angeles after the professional season and he wanted to meet me, so he came by the hotel where I was staying just to say hi. I didn’t play against him until we were both in the NBA.

CC: Friends?

KAJ: Oh absolutely.

CC: Wilt Chamberlain - complicated relationship?

KAJ: Yeah, you know he was someone who was a hero of mine when I was in high school and he’d come to Harlem and let me hang out with him. He was someone I admired and then I had to compete against him. After I broke his scoring record, all of a sudden he started taking shots at me in the press.

Kareem is the most prolific scorer in NBA history. He scored 38,387 points. Karl Malone is now second, with 36,928; Michael Jordan has 32,292 and Wilt retired with 31,419. Julius Erving scored 30,026 while playing on both the ABA and the NBA.

CC: You wrote a tough piece on Wilt in the book detailing your final season, and you took umbrage with his support of Richard Nixon…

KAJ: I didn’t agree with him. It got a little nasty after I broke his record and he became very critical. It was not a good time for us.

CC: Did you become friends again?

KAJ: Yeah, we buried the hatchet. I’ll be the first to tell you, I couldn’t eclipse him. I was fortunate to be able to last long enough to break his scoring record, but that’s just one small aspect of his career.

CC: Everybody asks who is the best basketball player ever? In your book you mention Connie Hawkins being a mixture of both a great street basketball player - a star at the Rucker’s Tournament on the courts of Harlem - and a great NBA pro?

KAJ: Connie did great things...time went fast for him...he was never in great shape. He didn’t have that kind of dedication. Oscar Robertson I think certainly fits the bill.

CC: Oscar did a better job....comes closer to being the greatest player?

KAJ: Yeah. Oscar was not only great, he made everyone with him great, too.

CC: Was Connie Hawkins a wasted talent?

KAJ: I don’t think it was wasted, but he didn’t shine as brightly as he could have. Dr. J (Julius Erving) had a lot of Connie’s physical attributes, but took them a lot further just because of his dedication. He was in much better shape and more determined.

Connie Hawkins was limited to only seven years in the NBA because of a college-age betting scandal. He spent what could have been his greatest years performing with the Harlem Globetrotters and playing in smaller leagues. A star with the Phoenix Suns, he is a member of the Hall of Fame.

CC: Your first hook shot, you were nine-years-old. The sky-hook?

KAJ: There wasn’t much sky to it, but I got it off anyway. I missed my first hook shot.

CC: You made a lot of them.

KAJ: I worked real hard at it for a long time.

CC: Why don’t other people do the sky-hook?

KAJ: It’s not sexy. The kids, they look at Michael Jordan or Dr. J and they want to play the game like that. I wanted to play like Elgin Baylor...then I realized how the hook works.

CC: What are the mechanics of the sky-hook?

KAJ: The shot is the same every time. You need to get your back to the basket and keep the ball between you and your opponent. You get lift and turn your body toward the hoop, stretch to your greatest height and extend your arm. You shoot the ball off the tips of your fingers when you get to the highest point.

CC: Did anyone ever block it?

KAJ: No. No one guarding me ever blocked it. I blocked a few, but no one blocked mine.

CC: You scored 38,000 points with the shot the Milwaukee Bucks announcer first named the sky-hook.

KAJ: Right, but you know when I started playing I wanted to be Elgin Baylor. I didn’t want to be Bill Russell. After what I learned about the game, I saw that somebody with Bill Russell’s physique and athletic ability could dominate the game in a certain way, and I saw I had to compare myself to him rather than Elgin Baylor.

CC: Magic Johnson?

KAJ: One of the greatest point guards ever, similar to Oscar Robertson, but bigger and different in style.

CC: Are you guys close?

KAJ: Not very. We’re friends. He’s very much into his business thing now.

CC: Will you ever be a head coach in the NBA?

KAJ: Head coaching prospects don’t look bright. There are many reasons. I got into coaching late. My playing career lasted twenty years and I was burned out when it was over. I wanted to get away. It took me a couple more years to realize I wanted to get into coaching. And, I also had a reputation for being prickly.

CC: Did you deserve the reputation?

KAJ: I don’t think so...I don’t know...I got tired of the same questions about points and rebounds. I have learned as a coach that it is important to play the game and explain the game both...I lacked perspective.

CC: Your teammates called you Cap or Captain.

KAJ: I was honored to be called Captain. I appreciated what it meant...every kid, no matter their sport, dreams of leading his team in the big game. I saw myself at the head of the cavalry...it was a privilege to be the ‘go-to’ person.

CC: You’ve started the Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Foundation for the purpose of mentoring young people.

KAJ: We’ve got to do something. Young people today want a better life, but we’re not making it possible for them to get there. It is absolutely essential to coordinate the efforts and the funding of government and private organizations to provide safe options for young people to participate in our society.

CC: Good luck.

KAJ: Thank you.

The first of the mentoring centers being sponsored by the Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Foundation will be named in honor of Jazz musician, Thelonious Monk.

|